Several opinion articles have noted that we must reverse this trend. The justification, in line with the traditional economic theory, is that the Indian government and corporate sector need money to fund their investment plans, which would drive economic growth. Also, there is concern that household debt may be approaching unsustainable levels.

How valid are these concerns? What may be the reasons, and should we be worried?

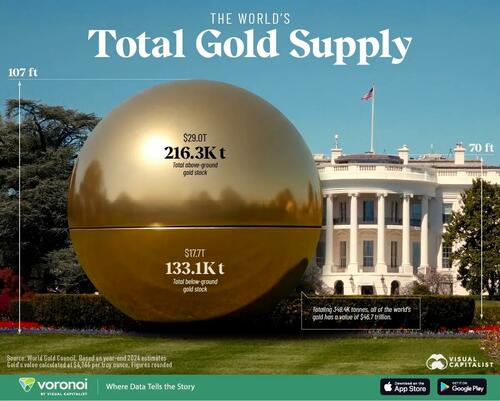

First, we do not yet have data for the last year on household (physical) savings in the form of real estate and gold. Since households’ borrowing for housing loans has been strong, their real estate holdings will likely have risen. Post-demonetization, if real-estate transactions are mostly in the formal sector, then formal financial markets would have seen an increased share. Further, families have been borrowing to finance vehicle purchases, another class of durable assets. In 2022-23, outstanding vehicle loans from banks grew 25%. Those by large vehicle financing non-banking financial companies outpaced bank lending significantly.

Second, in the aftermath of covid, an economic growth revival depended on household behaviour. Purchases of consumer durables, automobiles and homes had a key role in the recovery. Without this, corporate investment would not have returned. Saving is deferred consumption, and to kick-start the economy, we needed households not to delay consumption.

Third, Indians have been saving more in the stock market and through mutual funds. When asset prices—stocks and real estate—rise, people feel wealthier and may save less than they ought to. They also experience realized capital gains on the sale of equity, which go unaccounted as financial savings.

Fourth, the government now provides health insurance up to ₹500,000 annually to low-income individuals. An unintended consequence of this can be lower precautionary savings. It is rational for households, especially those with relatively low incomes, to spend more out of their incomes, especially if they are not rising at a robust pace.

Fifth, the formal economy has seen steady expansion. Those employed in it typically have access to retirement and pension funds. In 2022-23, the net addition to employee provident fund subscribers was 13.9 million, compared to around 12.2 million and 7.7 million in the previous two years. Given their contributions to their retirement funds, people may miscalculate the additional savings needed post-retirement.

Sixth, have household borrowings reached an unsustainable level? Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that on average, household borrowing, while having risen lately, is still less than 10% of household income. In fact, net household financial savings seem to be still about 20% of household income, calculated roughly as household consumption from GDP plus household savings.

Averages, of course, can be misleading. Among households, savers and borrowers may be different. Incomes and accumulated savings of those who take mortgage loans may be much lower than non-borrower incomes, with a higher risk of default. But then the question is this: Do tax incentives and government policies favour home ownership, making it attractive to take a home mortgage?

Buying a house is attractive because of the standard deduction one can claim on taxable income and also an interest subsidy. The government wants ‘housing for all,’ for which it facilitates access to affordable homes through a credit-linked subsidy scheme. If we don’t want Indians to save in real estate, then we need to alter this policy.

Seventh, if families spend more or save in physical assets, then corporate revenues and the government’s tax collections both rise. They ought to save more. Household savings’ contribution to overall savings is likely to decline and that of corporate savings increase (bit.ly/3LOu9jp)

Eighth, international debt flows can fund part of the government’s deficit instead of forcing households to save more. Foreign ownership of Indian government bonds is much lower than that of our emerging market peers. Inclusion in the JP Morgan EM Bond Index could bring in around $30 billion by early 2025. Potential inclusion in the FTSE EM and Bloomberg Barclays EM bond indexes could further increase debt inflows.

Finally, inflation must be controlled to help corporations and households lower their spending. Apart from raising the cost of essentials, high inflation raised borrowing costs in fiscal year 2022-23, as RBI’s repo rate went up from 4% to 6.5%. Controlling inflation would reduce interest burdens and improve savings.

Compared to their parents, today’s young may procrastinate far more when it comes to savings. Given their insurance cover and pension contributions, they may wrongly believe that they don’t need to save much for the future. They may also fail to adequately assess the probability of adverse shocks, such as a job loss or health crisis, due to overconfidence in the economy and themselves.

Eventually, households may have to save more. But in the meantime, expecting them to simultaneously spend and save more as a share of income is inconsistent.

“Exciting news! Mint is now on WhatsApp Channels 🚀 Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest financial insights!” Click here!

Download The Mint News App to get Daily Market Updates.

More

Less

Updated: 09 Oct 2023, 09:46 PM IST