Spain was a first-rank European energy round 1500. However its financial development was minimize quick on the finish of the sixteenth century, giving technique to a sustained decline after which falling behind Western Europe (Prados de la Escosura et al. 2020). Whereas it has been recognized for a while that there’s “extraordinarily considerable proof pointing to a decline in herding, agriculture, trade, and commerce within the Spain of the seventeenth century” (Vives 2015: 411), there’s presently no consensus within the literature close to the underlying trigger for Spain’s decline.

Opposite to a lot of the English-language literature, which blames the decline – financial and scientific – of Iberia on preliminary establishments, weak state capability, or faith (Henriques and Palma 2019), in a latest paper (Charotti et al. 2022) we argue that the underlying key explanation for the Iberian decline was a useful resource curse related to the endowment of valuable metals within the Americas. From an financial perspective, the inflow of metals made tradable industries much less aggressive as a result of inflation led to an appreciation of the true trade fee. Because of this, imports elevated and exports had been a lot lowered (Drelichman 2005). As well as, there was a political impact: establishments deteriorated as energy turned extra absolute and the state was captured by international pursuits and inside lobbies (Vives 2015, Drelichman 2007). Whereas earlier analysis has lined completely different facets of the useful resource curse in early trendy Spain, no trendy empirical analysis of the long-run counterfactual was beforehand out there. That is what we do in our paper.

We depend on macroeconomic time collection information from latest developments within the historic nationwide accounts literature. The info include GDP and price-level estimates constructed from detailed info on market costs for items, wages, and land rents collected from a wide range of sources at an yearly frequency. We mix time collection spanning three centuries from completely different Western European international locations, specifically Spain (Álvarez-Nogal and Prados de La Escosura 2013), the UK (Broadberry et al. 2015), France (Ridolfi and Nuvolari 2021), Italy (Malanima 2011), and Sweden (Krantz 2017).

We make use of the augmented artificial management technique to analyse the impression of the inflow of the American treasure (see Abadie 2021 and Ben-Michael et al. 2021 discussions). Extra particularly, we assemble a ‘doppelganger’ that, for the post-treatment interval, will be interpreted because the anticipated trajectory of the Spanish economic system if the nation had not been the primary receiver of those valuable metals. This artificial counterfactual is estimated as a weighted common of every end result variable of curiosity for different Western European international locations, with the weights being decided by pre-treatment similarities.

In Determine 1 panel (a), the collection represented by the darkish strong line reveals the true evolution of the worth degree (measured in silver items) for the Spanish economic system, whereas the sunshine dashed line reveals the estimated artificial counterfactual. Accordingly, the distinction or the hole between actual and artificial Spain represents the therapy impact, as depicted in panel (b). Our findings spotlight that, in contrast with an artificial counterfactual, the worth degree in Spain elevated by as much as 200% extra by the mid- seventeenth century.

Determine 1 Hole and the worth degree in silver (index 1500=100)

Notes: We used the ridge augmented artificial management technique. The shaded space within the (a) determine is one customary deviation of the distinction between the result of curiosity and the estimated counterfactual through the pre-treatment interval. The worth degree index hole in determine (b) is outlined because the distinction between the noticed value degree index and the estimated counterfactual.

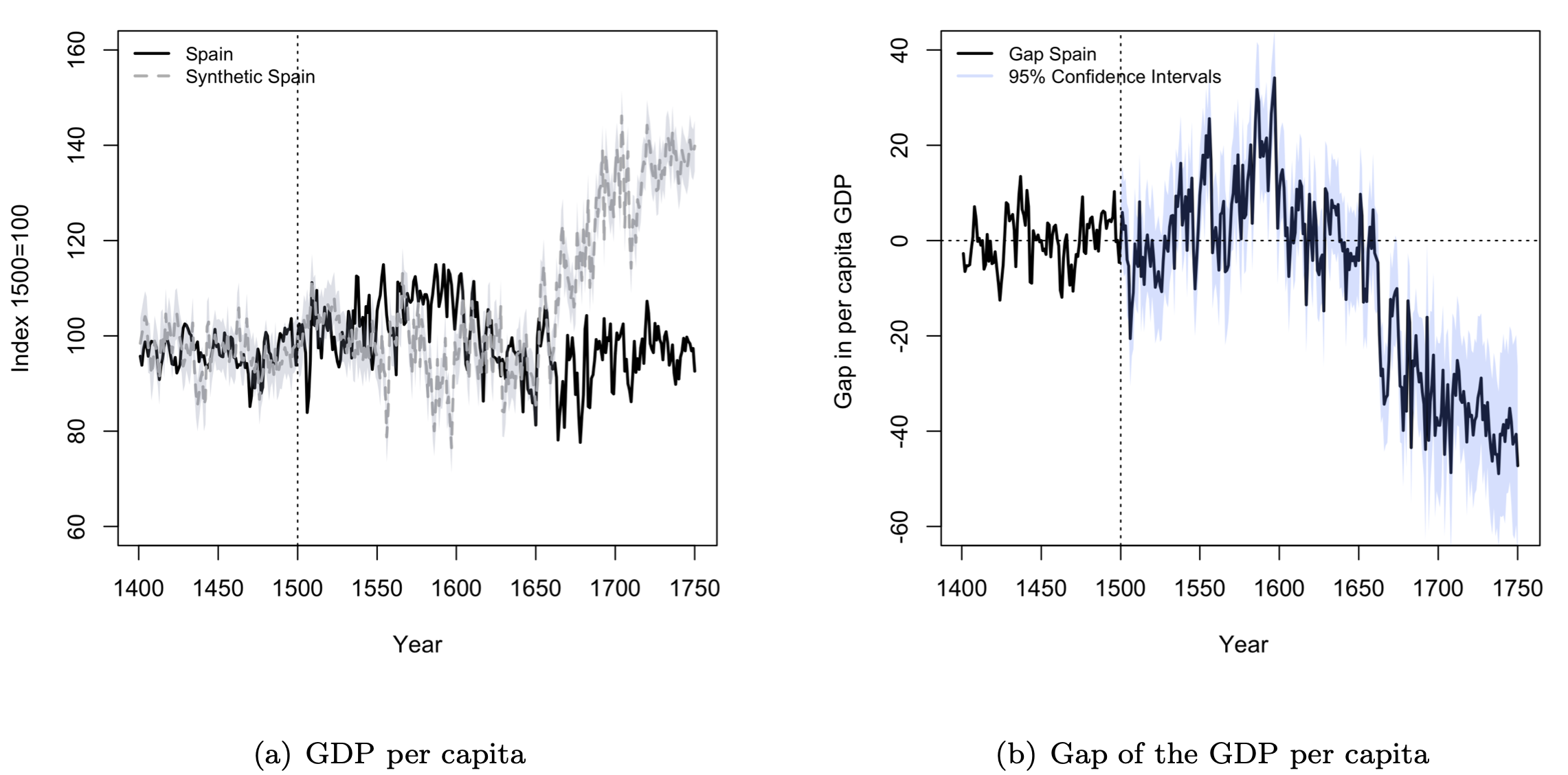

With respect to GDP per capita, as proven in Determine 2, Spain outperformed different European nations for round a century: by 1600, it was near 40% increased than in its counterfactual. Nevertheless, this impact was reversed within the following 150 years: by 1750, GDP per capita was 40% decrease than it will have been if Spain had not been the first-wave receiver of the American treasure.

Determine 2 Hole and GDP per capita in 1990 G-Okay {dollars} (index 1500=100)

Notes: We used the ridge augmented artificial management technique. The shaded space within the (a) determine is one customary deviation of the distinction between the result of curiosity and the estimated counterfactual through the pre-treatment interval. The hole in per capita GDP in determine (b) is outlined because the distinction between the noticed GDP per capita index and the estimated counterfactual.

We argue that the mechanism behind the patterns noticed in Spain was a useful resource curse, which had each an financial (‘Dutch illness’) and political dimension (Henriques and Palma 2019). Our outcomes additionally spotlight the truth that financial forces can have distributional and everlasting penalties in the long term.

References

Abadie, A (2021), “Utilizing artificial controls: Feasibility, information necessities, and methodological facets”, Journal of Financial Literature 59(2): 391-425.

Álvarez‐Nogal, C and L P De La Escosura (2013), “The rise and fall of Spain (1270–1850)”, The Financial Historical past Evaluation 66(1): 1-37.

Ben-Michael, E, A Feller and J Rothstein (2021), “The augmented artificial management technique”, Journal of the American Statistical Affiliation 116(536): 1789-1803.

Broadberry, S, B M Campbell, A Klein, M Overton and B Van Leeuwen (2015), British financial development, 1270–1870, Cambridge College Press.

Charotti, C, N Palma and J Pereira dos Santos (2022), “American treasure and the decline of Spain”, The College of Manchester Economics Dialogue Paper Collection EDP-2201.

Drelichman, M (2005), “The curse of Moctezuma: American silver and the Dutch illness”, Explorations in Financial Historical past 42(3): 349–380.

Drelichman, M (2007), “Sons of one thing: Taxes, lawsuits, and native political management in sixteenth-century Castile”, The Journal of Financial Historical past 67(3): 608–642.

Henriques, A and N Palma (2019), “Comparative European establishments and the ‘Little Divergence’, 1385–1800”, VoxEU.org, 10 December.

Krantz, O (2017), “Swedish GDP 1300-1560: A tentative estimate”, Lund College, Division of Financial Historical past.

Malanima, P (2011), “The lengthy decline of a number one economic system: GDP in central and northern Italy, 1300–1913”, European Evaluation of Financial Historical past 15(2): 169–219.

Prados de la Escosura, L, C Álvarez-Nogal and C Santiago-Caballero (2020), “Progress Recurring in a Preindustrial Financial system: Spain in a Half-Millennium Perspective”, VoxEU.org, 7 Might.

Ridolfi, L and A Nuvolari (2021), “L’histoire motionless? A reappraisal of French financial development utilizing the demand-side method, 1280–1850”, European Evaluation of Financial Historical past 25(3): 405– 428.

Vives, J V (2015), Financial Historical past of Spain, quantity 2416, Princeton College Press.