- There’s a cushion of sizeable unrealized/imbedded beneficial properties within the nation’s housing inventory and enormous unrealized beneficial properties within the US Inventory Market.

- The US has a really sturdy industrial/company base that has typically improved their steadiness sheets by rolling over into cheap debt over the past 5 years, and which have maintained excessive revenue margins.

- We have now a strong and tight labor market—with stable wage will increase a spotlight of the final a number of years. Importantly within the final 60 years the US has by no means had a recession and not using a previous spike in preliminary jobless claims.

- The US unemployment charge stands at 3.6%—the bottom stage because the begin of the pandemic and solely 0.1% above the 50-year low of February, 2020.

- Some necessary parts of inflation are moderating—the costs of most commodities have fallen significantly over the past 2 1/2 weeks.”

All good factors however let me add a caveat. Issues may be true within the mixture however painfully completely different in particular instances. Sure, family financial savings are up, however not for everybody. Half the nation has lower than $400 in financial savings. One-bedroom house rents are close to $1,500 in lots of locations.

Ditto for companies. The common firm has a greater steadiness sheet, however many aren’t common.

Shopper Shift

The true query mark right here is client spending—how a lot it drops and how it drops. We’re within the thick of earnings season and studies from retailers aren’t good. Walmart (WMT) is broadly watched, not simply by its personal buyers, however as a client well being indicator. Its sheer measurement and nationwide scope reveal quite a bit concerning the economic system.

Walmart’s newest is partly unsurprising: Persons are spending extra on meals and gas. The haunting half is that they’re additionally spending much less on issues like attire, furnishings, and different non-essential items. Worse, these occur to be the identical items that had been scarce on account of provide chain snarls. Now that they’re lastly on the cabinets, individuals don’t need (or can’t afford) them. Retailers are overstocked and chopping costs on slow-moving items whilst they increase costs on others.

The larger level right here is that client choice is altering… once more. Recall what occurred with COVID: Folks shifted their discretionary spending from companies to items as a result of the companies have been unavailable or perceived as dangerous.

Now the alternative is going on. Retailers are lastly getting tailored to new demand patterns simply because the demand goes away. In the meantime airways and trip spots, which had suffered as so many individuals stayed near house, are clogged with extra clients than they’ll deal with.

Shopper woes are additionally enterprise woes. Bruce Mehlman summed it up with this from his newest slide deck.

Supply: Bruce Mehlman

All that looks bad, and it is, but keep it in perspective. Businesses can meet rising costs in several ways. The most common is to cut some other kind of less essential cost or try to shift it onto your suppliers. That’s harder than it used to be; many companies were already running pretty lean after going into COVID survival mode. This from Quill Intelligence:

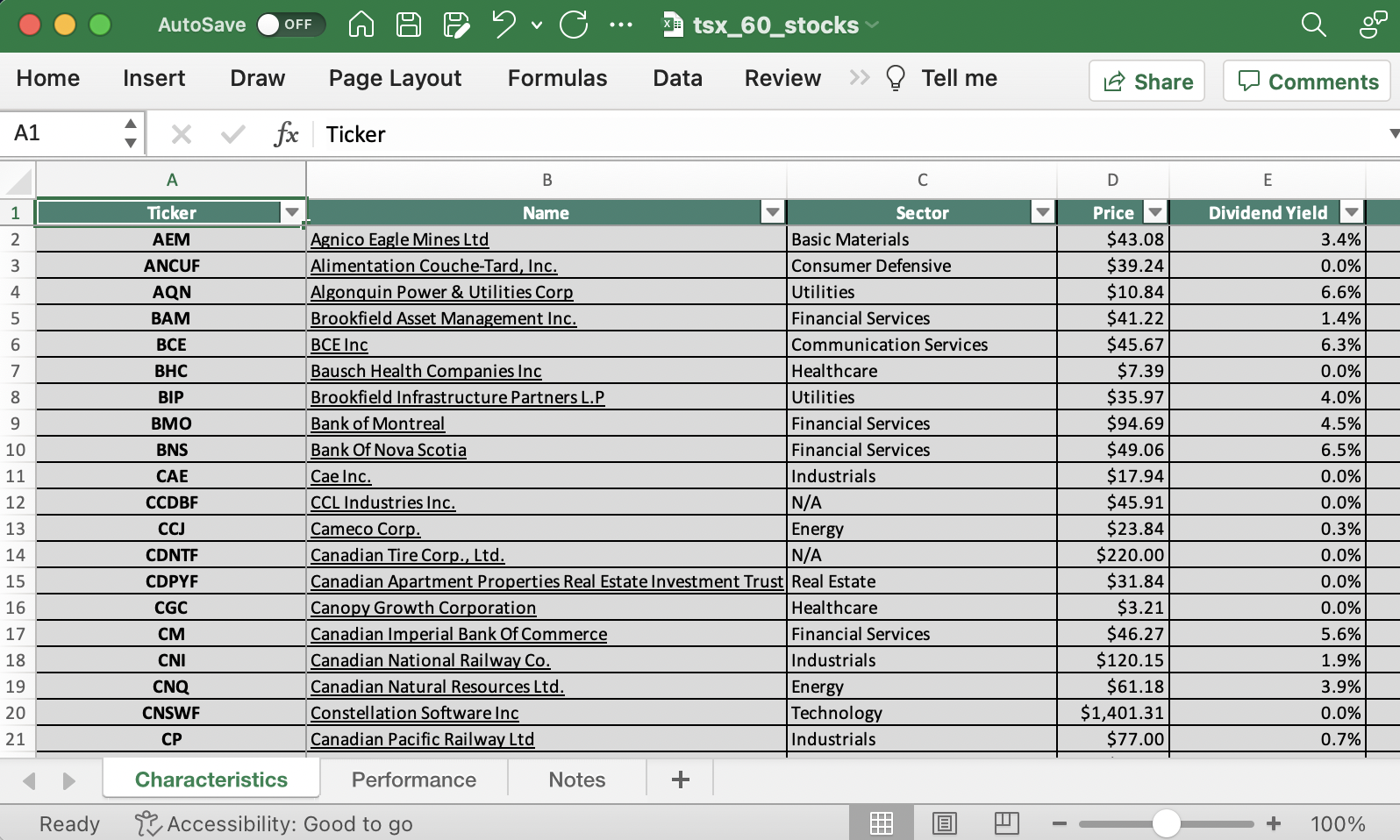

Source: Quill Intelligence

Note the upper right box. Consumers are switching from goods to services.

As for squeezing suppliers… right now they’re happy just to have suppliers. I saw a story from Japan that Toyota is skipping its normal semiannual review and won’t press suppliers for lower prices. In some cases, it may actually pay more to make sure the essential suppliers stay in business.

The other alternatives are to raise selling prices—which can easily backfire when customers are already stretched—or accept lower profit margins. That looks increasingly likely for many companies. Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Proctor & Gamble, and Kimberly-Clark are continuing to raise prices.

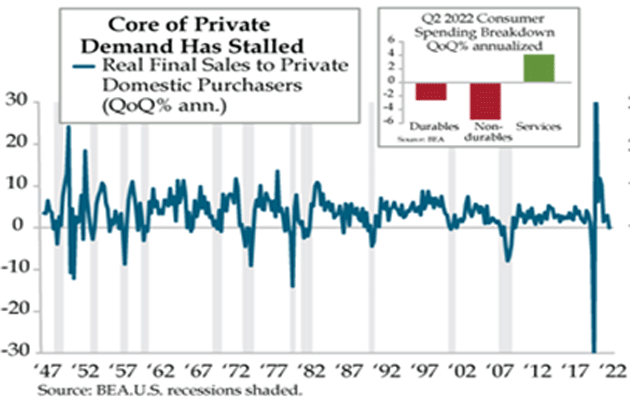

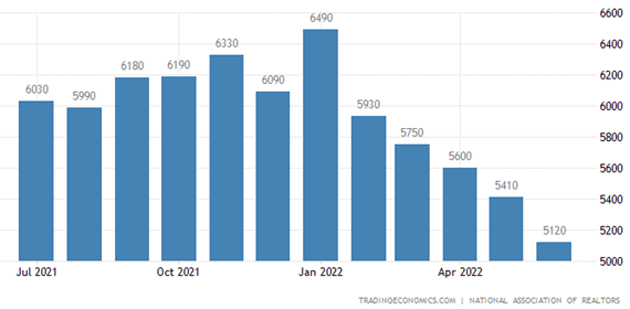

The worst-hit businesses will be those most exposed to higher interest rates on top of all the other rising prices. Yes, that means housing. That boom may not turn into a crash, but it has room to soften quite a bit, and seems to be in the early stages of doing so. It’s starting to show in both existing and new home sales.

Source: Trading Economics

Source: Mortgage News Daily

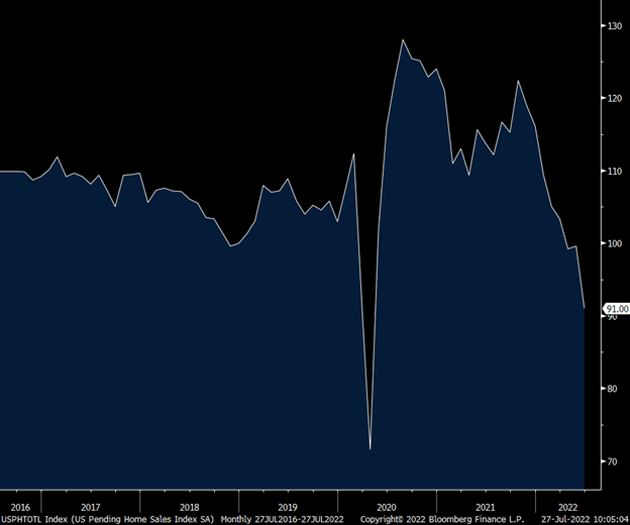

And Pending Home Sales are plunging.

Source: Peter Boockvar

Note that housing drives many other segments like furniture, paint, appliances, etc. These also suffer when home sales drop.

All this is consistent with a mild recession scenario, which is what we seem to be experiencing so far. Consumer spending softer but not too much. Unemployment rising but mostly in financing-dependent segments like housing and autos. Energy prices are staying high, but people learn to manage them. None of this is good but it could be far worse.

Unfortunately, that not-so-bad near-term outlook collides with some broader forces that are still coming. It is likely that the third quarter will be even softer than the previous two, as the Fed will continue to raise rates at the next three meetings.

Longer and Deeper

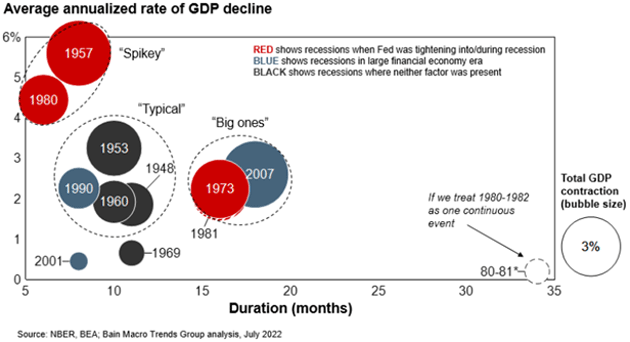

Bain Macro Trends Group makes the case that this recession will be most like the 2007 recession. Here’s a bit from their longer report.

“As we discussed in the first piece in this series, the current macroeconomic climate bears a notable similarity to the climate preceding the recession of 2007–2009. This is also the only recession in recent history that resembles (in depth, duration, and pace) those of previous high-inflation eras in which the Fed tightened into the contraction (e.g., 1973 and 1981). As Figure 2 illustrates, the recessions of 1973, 1981, and 2007 are a cluster by themselves with respect to duration and severity. [Note: The 1981 recession is almost hidden in this cluster graph by the 1973 recession. It’s there.]

“Because of these similarities, we believe companies must take seriously the possibility that this recession may repeat key elements of the recession of 2007–2009.”

Investors are looking at the “dot plots” to see when the Fed might stop tightening and maybe even ease, as that would be a signal to buy. Maybe yes, maybe no. From David Rosenberg (flagged by Peter Boockvar):

“Remember this: The Fed went on hold in February 1989, and while there was a nice tradable rally, the reality is that the low in the equity market wasn’t turned in until October 1990—twenty months after the pause. The Fed stopped tightening in May 2000, and the market low didn’t come until October 2002, over two years later. And the Fed moved to the sidelines in June 2006, and the lows didn’t come until March 2009.” I’ll add this, the Fed started cutting rates in January 2001 and the market bottomed in October 2002. The Fed started slashing rates in September 2007 and the market bottomed in March 2009.”

Productivity Problem

One final thought. We use GDP as a proxy for economic growth. What it really measures (with a lot of flaws) is output, or production. That’s the “P” in GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

At the most basic level, GDP is simply the number of workers a country has times the average worker’s output. That’s what we call productivity. A worker takes something—knowledge, building materials, whatever—and adds value by producing something new. Combine all that new value and you get GDP growth.

If you want more GDP, math says you need some combination of more workers and/or more per-worker productivity. Postwar US economic growth happened for both reasons, but mainly productivity growth.

With population growth slowing, GDP has been more dependent on productivity growth. This is becoming a problem. Edward Chancellor explained why in the interview I mentioned last week. Here’s another part I didn’t quote:

“By aggressively pursuing an inflation target of 2% and constantly living in horror of even the mildest form of deflation, they not only gave us the ultra-low interest rates with their unintended consequences in terms of the Everything Bubble. They also facilitated a misallocation of capital of epic proportions, they created an over-financialization of the economy and a rise in indebtedness. Putting all this together, they created and abetted an environment of low productivity growth.”

Businesses have an interest in making their workers as productive as possible. They do this in various ways, including skill training and labor-saving technology. That doesn’t have to mean fewer workers. If adding robots to your factory triples production without having to hire more people, it also triples productivity. That’s good; it keeps prices down and helps more jobs emerge elsewhere.

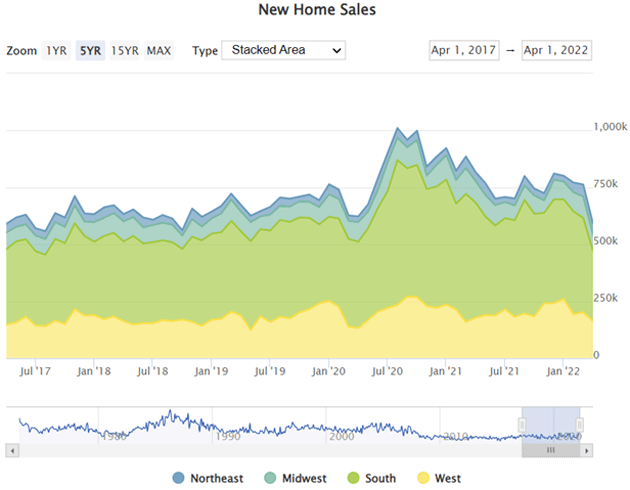

But as Chancellor says, the Fed’s persistently low interest rates discouraged this process. We see it in the data. The Bureau of Labor Statistics measures productivity quarterly. Here’s the beginning of their last report on June 2. (The next one is August 9, by the way.)

Nonfarm business sector labor productivity decreased 7.3 percent in the first quarter of 2022, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today, as output decreased 2.3 percent and hours worked increased 5.4 percent. This is the largest decline in quarterly productivity since the third quarter of 1947, when the measure decreased 11.7 percent.

They’re talking about a quarter when GDP actually fell, so it’s no surprise output decreased. The surprise is that more work hours produced less output. That’s not how it should go. And that this was the worst since 1947 should concern us.

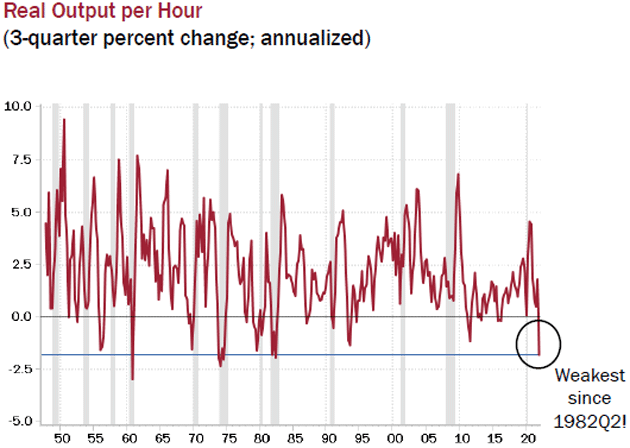

Here’s a slightly different view, again thanks to Dave Rosenberg. He illustrates the change in productivity growth on a per-hour basis. By that measure it’s the worst since 1982.

Source: Rosenberg Research

That’s a noisy chart but if you take out the last two recession spikes, it looks like productivity has been broadly declining since the mid-1990s. What might have caused that?

As they say, correlation isn’t necessarily causation. But it may be relevant that this is about when the “Greenspan Put” went from a novel surprise to something traders simply expected. The 1997 Asian debt crisis and 1998 Long-Term Capital Management bailout confirmed we had a new kind of Fed. So I think Chancellor is right to pin productivity declines on the Fed, at least in part.

Now, add in the demographic factors that are shrinking the workforce. And on top of that, add the not-insignificant number of pandemic-driven early retirements and “Long COVID” disabilities. That means we need more productivity from the remaining workforce.

This is looking like a challenge. United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby said in a recent interview that sickness-related absenteeism is now so high, he thinks airlines will have to permanently add 4%‒5% more workers just to accomplish the same amount of work. That’s staggering and, if correct, I see no reason to think it won’t apply in many other industries.

If a company now needs, for example, 105 workers to produce the same output that used to be possible with 100 workers, it is negative productivity growth. Not good for profits and certainly not good for GDP.

Could automation help? In some cases, probably so. But between microchip shortages and higher financing costs, that’s not getting any easier. Nor does it solve every industry’s problem. McDonald’s CEO Chris Kempczinski talked about automation on the company’s last earnings call.

“We’ve spent a lot of money, effort, looking at this. There is not going to be a silver bullet that goes and addresses this for the industry… The economics don’t pencil out.”

If any restaurant chain could make automation work, it would be McDonald’s. The CEO says it isn’t a silver bullet. That means his company—and many others—will stay dependent on human workers, who are on average getting less productive per hour worked.

Where does that lead? Nowhere good. I have faith our human ingenuity will find solutions, but meanwhile productivity is a giant problem.

It’s likely going to cap GDP growth at a level none of us will like—which is also what you would expect with the massive US debt load. Everywhere debt rises (Japan, pick a country in Europe, the US), GDP slows. Which is precisely what Lacy Hunt and I and others have been saying for years.

Looking back at the period between the 2008 crisis and COVID in 2020, we all wondered why GDP seemed stuck so low. That era’s sluggish growth wasn’t a recession, per se, but it was unlike past recoveries.

Now, I wonder if we’ll have a similarly extended period of even lower growth. After we get through this recession, GDP growth may slow to 1%. That would be a recession/recovery like no other in memory.

At the rate weird things are happening, I wouldn’t rule it out.

Cleveland and British Columbia

I’m scheduled to be at the Cleveland Clinic with Dr. Mike Roizen and team for at least two days in mid-August. They will check out my body doing every rude thing known to man: tubes, scopes, lasers, oh my. COVID delayed my check-up in 2020 so I’m overdue. My body feels it.

At the end of August, I get to check off one of my bucket list fantasies and go salmon fishing in British Columbia at a private camp, reachable only by helicopter. But the pictures look exciting. I’m looking forward to 40+-pound Chinook. I’m told they are catching nice-sized halibut at the same fishing holes. I’m not quite sure of the rules, but I hope to bring some flash-frozen fish home.

It’s time to hit the send button. I left more good material on the cutting room floor this week than I have in a long time. There is really a lot more to say on this topic. Maybe next time.

Have a great week and spend some time with friends and family! And as always, don’t forget to follow me on Twitter!

Your questioning how bizarre this recession will actually be analyst,

John Mauldin