This morning, the WSJ reported that “Consumers expect to see 4.1% inflation a year from now, the lowest such reading in two years and down sharply from its recent peak of 6.8%.”

There are some who believe this is good news, but as we pointed out in May, it’s a meaningless, lagging survey. In fact, it may be even worse than that, because it appears that some at the Federal Reserve actually believe the Fed’s own survey of consumers contains information. As we have previously shown (repeatedly), it does not.

At least, it does not contain valuable information providing insight into future inflation levels. What it does reveal is that the Federal Reserve is not current with the latest research on 1) What drives inflation; 2) The fallibility of surveys and polling data; 3) An updated understanding of behavioral economics and how human decision-making works.

Last we noted, Sentiment Surveys are generally useless; their most valuable moments occur at extremes, which are typically visible in hindsight. People have no ability to forecast things like what inflation will be like 1, 3, or 5 years hence. They can (arguably) extrapolate out current CPI a few months or quarters, but even that might be too generous. And while people’s expectations can factor into inflation, it is but one element out of many, and one that is easily changed.

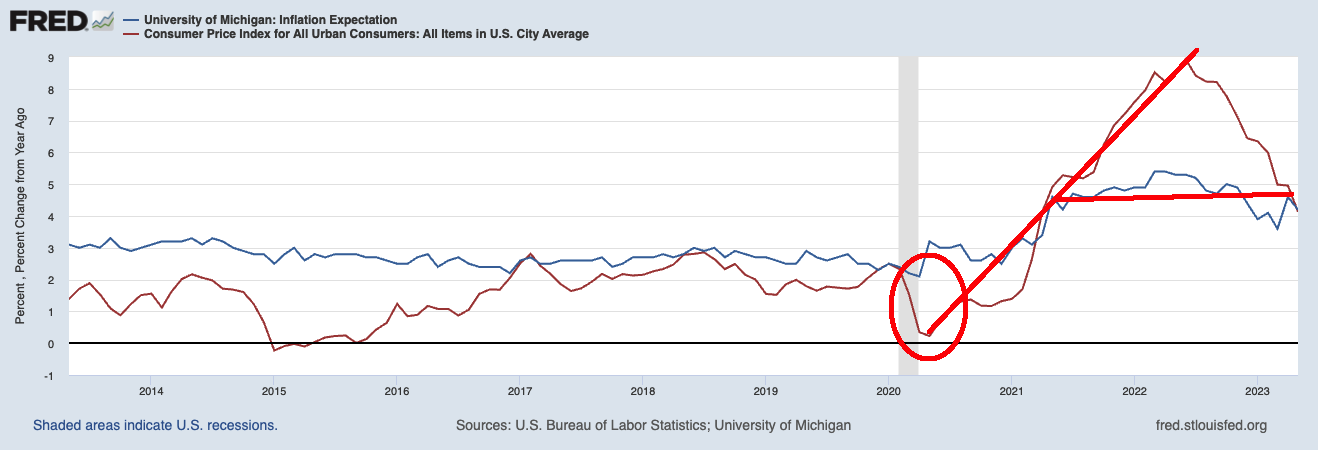

As the FRED chart below shows, consumers were quite sanguine about inflation at the beginning of its huge run-up in 2021; they were panicked about inflation at the peak, just as it was beginning its collapse. If you bought Inflation Futures based on Consumer expectations, you would quickly go broke.

To say this is a useful measure reveals an irrational attachment to an outdated standard. As Brookings explained, this traces back to the late 1960s work by Nobel laureates Edmund Phelps and Milton Friedman. They focused on inflation expectations due to the ties between inflation and unemployment. Persistently high inflation in the 1970s became unanchored, as long-running inflation led to higher wage demands. The phenomenon of the wage-price spiral persisted in the 1970s and 80s.

It seems to still be persisting among certain economists, who have ignored what occurred post-pandemic/post-fiscal stimulus: Despite CPI spiking higher, unemployment continued to fall.

Consider what occurred since the 1970s: Globalization increased, automation became widespread, and productivity increased dramatically. I suspect these factors are part of the reason why inflation and unemployment have decoupled. The other part is that the economy is just so different today than it was 50 years ago, that using a 1970s analog is a recipe for failure.

The entire concept of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (which won a Nobel prize for Eugene Fama) was that what people say about anything is far less valuable than what they do, especially with their hard-earned dollars. Whether they invest it in the market or buy inflated consumer goods is itself a source of valuable information; certainly much better than asking them what they thought inflation might be sometime in the distant future.

People who should know better pay way too much attention to Inflation Expectations. The charts above show that they shouldn’t…

Previously:

Inflation Expectations Are Useless (May 17, 2023)

Transitory Is Taking Longer than Expected (February 10, 2022)

Nobody Knows Nuthin’ (May 5, 2016)

How News Looks When Its Old (October 29, 2021)

Predictions and Forecasts

Nobody Knows Anything

Source:

Good News for the Fed: Shoppers See Lower Inflation on the Horizon

By Christian Robles

WSJ, July 3, 2023