Alphotographic/iStock Unreleased via Getty Images

It’s the place where middle-aged codgers like me used to go on a Saturday morning to buy records and it’s where generations of people before us got their newspapers.

But today, things are very different. WH Smith’s (OTCPK:WHTPF) high street business has been in decline for years and its stores have repeatedly been voted the worst shops on the high street. The pandemic delt the business a mighty blow and it was forced to raise new debt and equity just to stay afloat.

However, the higher growth travel business has performed much better and is now actually bigger than the high street business, so is WH Smith really a high street dinosaur, or does it have good potential as a dividend growth investment?

WH Smith has been a convenience retailer for more than 200 years

The business that became WH Smith started out as a small newsagent, opened by Anna and Henry Smith in or shortly before 1792. That same year their second son was born and they named him William Henry Smith. Tragically, Henry Smith died a few months later and Anna was left with two young sons and a new business to manage by herself.

And manage it she did.

When her two sons (Henry and William) were old enough, they started working in the business and in 1812 it was valued at £1,280, a tidy sum just over two hundred years ago. When Anna died in 1816, she left the business to her sons and they formed an official partnership as H & W Smith.

By 1821 the business had moved to larger premises and was selling stationery, newspapers and books, as they still do some 200 years later. The brothers also opened a reading room, where customers could read their favourite publications for a fee.

From these humble origins, the business became a national treasure after a series of major breakthroughs.

Breakthrough #1: Revolutionising the speed of newspaper delivery

The first major breakthrough came when William, who would eventually take over the business, decided to focus on newspaper distribution. In the early 19th century, it could take more than a day for newspapers to get from the printing press to the reader, so this was an area ripe for disruption.

The existing system relied on horses and carts. They would pick up the morning papers from the publisher and get them to the inter-town or inter-city horse and coach offices in time to catch the overnight coach.

William’s revolutionary idea was to use fast horses, small carts and brave riders to get the papers to the coach office in time to catch the midday coach. Occasionally, the firm would hire its own horse and coach and deliver papers directly to the customer, beating even the midday coach. And when King George the Fourth died, H & W Smith hired its own boat and delivered the news to Dublin a full 24 hours ahead of the Royal Mail.

In short order, rapid newspaper delivery became the firm’s core business, transforming H & W Smith from a small newsagent, bookstore and stationer in London to a much larger and nationwide newspaper distribution business.

Breakthrough #2: Riding the coattails of the Victorian railway boom

By the mid-19th century, Henry had left the business and William had been joined by his son, so the business was renamed W. H. Smith & Son, a name it retained for almost 130 years until it was shortened to WH Smith in 1973.

This was the era of the Victorian railway mania, and as railways and railway stations began to pop up across the UK, more and more people began travelling by train. Unfortunately, most passengers found themselves sat in an uncomfortable carriage, often without a roof and usually with nothing to read.

This was another golden opportunity and WH Smith grabbed it with both hands when, in 1848, it opened a small newspaper and book stall in Euston station. More stalls followed, and over the next 60 years, buying something to read from one of WH Smith’s railway stalls became a part of daily life for millions of commuting Brits.

Breakthrough #3: Expanding from railway stalls to high street stores

The third and final major breakthrough came in 1905, when the company faced stiff competition for its railway stalls. As leases came up for renewal, rents were pushed up and eventually the firm decided that enough was enough. A decision was made that for every stall that failed to renew its lease on acceptable terms, a new store would be opened in the local high street, selling newspapers, books and everything else previously sold in its railway stalls.

The high street business was built almost overnight, and by the beginning of 1906, there were well over 100 WH Smith stores in every significant town along the major railway routes.

Many customers followed WH Smith into the high street and the stores were a success. More importantly, with a larger footprint and higher footfall than a railway stall, WH Smith’s high street stores returned to the broader range of products sold in its 19th century stores, namely books, newspapers, stationery and convenience items for shoppers on the go.

Eventually this expansion into the high street went too far. In the 1970s and 1980s, WH Smith entered a period of “diworsification”, running businesses as diverse as Do It All (DIY stores), Waterstone’s (book stores) and Our Price (record stores).

By the early 2000s those businesses had been removed, but the company still had fingers in too many pies, including book publishing, several hundred outlets inside US hotels and a number of stores in Asia Pacific. All of that was in addition to the high street stores, the railway (and now airport) retail units and the newspaper distribution business. During this period, WH Smith was seriously underperforming on almost all fronts and venture capital firms were looking to acquire it.

The company was in crisis, but that crisis turned out to be a fantastic opportunity.

From stodgy high street retailer to lean, mean profit machine

As often happens during a crisis, WH Smith replaced its CEO. The new CEO was Kate Swann, previously Managing Director at Argos, and it didn’t take long for WH Smith to realise that Swann was something of a management genius, or at the very least, she was a no-nonsense implementer of sensible business fundamentals.

When Swann arrived in 2003, her initial review found that WH Smith was too diversified and too focused on maintaining its size rather than maintaining attractive profit margins and returns on capital.

Her plan was to refocus WH Smith around its core business:

“Building unique strength in a core business, no matter how small or narrowly focused, is the key to subsequent growth. In fact, sometimes the right strategy is even to ‘shrink to grow’, going back to the core of the core” – Chris Zook, Profit from the Core

With the patient not quite on life-support but not far off, Swann immediately began whipping the company into shape.

In 2004, she sold the US and Asia Pacific businesses as these were a distraction from the core UK business. She also sold off the book publishing business for similar reasons, leaving just the high street stores, the UK travel business and the newspaper distribution business.

In 2006 Swann struck again, spinning off the newspaper distribution business as Smiths News. This was a huge decision and a brave one, because newspaper distribution had been a key part of WH Smith since at least 1828. But it was also the right decision.

It was the right decision because physical newspapers were in decline, thanks to the internet, and any business delivering newspapers would suffer a similar fate. Fighting this decline would be a massive challenge and Swann already had enough of a challenge turning the high street business around.

While all this was going on, Swann made it clear that the high street business’s number one priority was return on capital, not revenue, and if raising profit margins and returns on capital meant selling fewer low-margin products or closing insufficiently profitable stores, then so be it.

The UK travel business was already performing well, so growth would remain its primary focus. In fact, in 2010, the travel business took its first tentative steps outside the UK, opening six stalls in airports or railways in Calais, Stockholm and other cities that were relatively close to the UK.

Over the next few years, profitability in the high street continued to improve, the UK travel business continued to grow and the international travel business started to grow even faster.

Today, WH Smith is primarily a travel retailer with a small high street business on the side

Let’s have a look at the WH Smith of today in a bit more detail.

High Street (34% of group revenues): To most people, WH Smith is a high street newsagent, bookseller, stationer and seller of snacks and convenience items you might pick up while you’re in the high street. This view is misleading because the high street business generates just a third of the company’s total revenues.

The travel business has overtaken the high street business partly because the travel business has grown very strongly, but it’s also because more people shop and read electronically and that has impacted high streets across the UK. This is reflected in the number of high street stores, which has fallen from 615 a decade ago to 527 today.

The high street division also includes WH Smith’s online businesses, whsmith.co.uk, funkypigeon.com and cultpens.com. Of these, personalised greeting card retailer Funky Pigeon probably has the most potential for growth and value creation.

UK Travel (37% of group revenues): In the UK, the travel business has almost 600 retail units in hospitals, railway stations and airports. Most of these are WH Smith units, but many are M&S Simply Food or Costa Coffee units that WH Smith operates as a franchisee.

International Travel (29% of group revenues): This division is primarily focused on airports and has grown organically from less than 100 stores in 2013 to more than 300 stores today in 30 countries, excluding the US. The US is a somewhat separate business that WH Smith has grown from nothing a few years ago to almost 300 stores today, mostly through the acquisition of travel retailers InMotion and Marshall Retail Group (MRG).

Given that WH Smith has been operating high street stores for more than 100 years and railway stalls for more than 150 years, the company easily passes one of my rules of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: The company should have a long history and deep expertise in its core markets

The three divisions above are focused on two primary goals:

- To be the world’s leading retailer of essentials for travelling customers

- To be Britain’s most popular high street stationer, bookseller and newsagent

As I see it, the strategy for achieving these goals has three main pillars.

(1) Focus on profitability: 20 years ago, WH Smith was selling too many low margin products and its cost base was too high, so an obvious but difficult first step was to stop selling high volume but low margin products like CDs and DVDs.

But that was just the beginning. With hundreds of high street stores, WH Smith effectively had an enormous petri dish where it could evaluate a wide variety of product combinations across every square metre of space in hundreds of stores. Over time, it developed the ability to gather that data and analyse it forensically in order to optimise store layouts and product choices so that profit margins and returns on capital were maximised.

In addition to this laser focus on space optimisation, the high street business became obsessed with efficiency and cost reduction.

For example, internal investments must earn satisfactory returns, so expensive store refits are rarely carried out. Instead, the poor condition of WH Smith’s high street stores is widely recognised and WH Smith has repeatedly been voted the worst shop on the high street.

However, most customers don’t really care if the stores are somewhat worse for wear. What they care about is being able to conveniently buy a book or magazine to read on the bus, some pens and paper for the kids or a snack to eat, and that convenience is what WH Smith’s high street stores provide.

WH Smith was also one of the first high street retailers to roll out self-service checkouts. More recently, it has begun to roll out “Just Walk Out” stores using technology developed by Amazon. These innovations free up more space to display products and of course they reduce the number of staff needed to run a store.

(2) Focus on travel: The high street business has improved dramatically over the last 15 years, but it still operates in a shrinking market. To escape this decline, WH Smith set its sights on becoming the leader in convenience retail for travelling customers in the UK and internationally. This makes sense because the leisure travel market is expected to grow faster than the overall global economy for at least the next several decades.

The travel business shares optimisation lessons with the high street business and this helps it generate more revenue per square metre than most competitors. Rents for travel units are tied to revenue, so higher revenues mean higher rents and that makes landlords (e.g. airports, railway stations and hospitals) happy. That, in turn, makes it easier for WH Smith to beat out the competition when landlords are looking for new tenants.

(3) Focus on landlords: In addition to pleasing travel landlords through high revenues and rents, another way to please them is to make their life easier by reducing the number of tenants they need to operate a variety of retail units.

For example, WH Smith can provide landlords with WH Smith stores, post offices and pharmacies, as well as M&S Food and Costa Coffee units. On top of that, it recently acquired the world’s leading retailer of tech gadgets in travel locations (InMotion) and another travel retailer with a special focus on designing unique retail units for airports and tourist destinations (MRG).

Given this broad offering, if a landlord wants to fill ten units with ten different retail propositions, WH Smith can run them all.

WH Smith was a metronomic growth machine before the pandemic struck

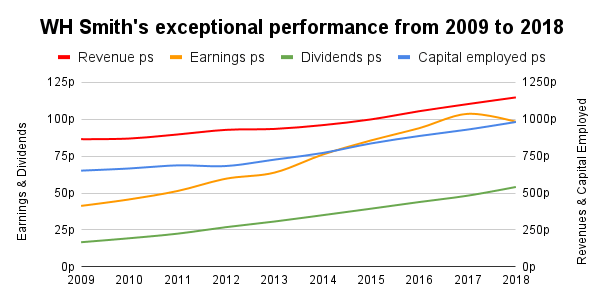

Before the pandemic, WH Smith’s performance was exceptional. Growth across revenues, earnings and dividends was metronomic, averaging 10% per year. That growth was entirely driven by the travel businesses and Funky Pigeon, which more than offset a decline in stores, revenues and earnings from the high street business.

This steady growth means that in 2018, WH Smith passed two of my investment rules:

- Rule of thumb: Capital (debt + equity), revenue, earnings and dividends per share should have a ten-year growth rate of at least 2%

- Rule of thumb: Capital, revenues, earnings and dividends per share should have grown consistently over ten years

Unfortunately, this impressive track record has been obliterated by the pandemic.

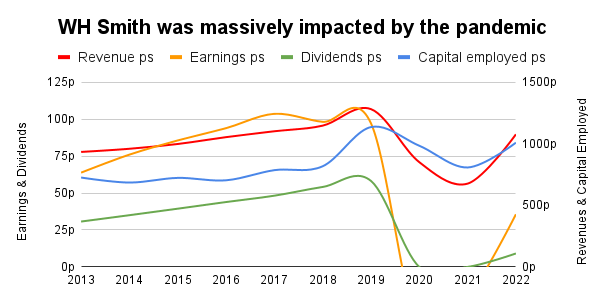

As a travel retailer, WH Smith generates most of its revenues and earnings from airport and railway units, and when the pandemic was in full swing, effectively all of these were closed for weeks at a time. The high street business faired marginally better, largely thanks to in-store post offices that were allowed to stay open.

Overall though, WH Smith took a very serious beating from covid to the point where it now fails my growth-related rules. This is a Yellow Flag, albeit a minor one because it was caused by a global pandemic that no company could reasonably prepare for.

The good news is that the pandemic is now over and travel revenues have almost recovered back to pre-pandemic levels. However, the high street business is still lagging 2019 by about 20%, mostly because more people now work from home. This means they’re less likely to walk past a WH Smiths on their commute and it seems likely that this is a permanent change.

Most of its recent growth was organic, but acquisitions played a key part in US growth

Having sold off various acquired businesses in the 1990s and early 2000s, WH Smith remained relatively acquisition-free for almost 15 years. But then, in 2018 and 2019, the company made two large acquisitions that transformed the size of its international travel business and its US business in particular.

InMotion: InMotion was acquired in 2018 for about £160 million. At the time, WH Smith’s average earnings were about £100 million, so InMotion was a “large” acquisition by my definition (it cost more than a typical year’s earnings). I don’t have a problem with slightly large acquisitions like this one, as long as there aren’t too many of them.

- Rule of thumb: Pay special attention to large acquisitions (those that cost more than an average year’s earnings)

From a business point of view, InMotion is the world’s leading electronics retailer in the travel retail market, so it’s closely related to WH Smith’s core business. That’s good, because acquiring businesses that have little to do with your core business is usually a bad idea, as WH Smith found out years ago after it acquired book publishers and DIY stores and then sold them at a loss.

- Rule of thumb: Acquisitions (especially large acquisitions) should be closely related to the core business

The acquisition of InMotion also made strategic sense because it gave WH Smith a foothold in the US market and it expanded the range of stores the company could offer landlords, making the overall proposition more attractive.

Marshall Retail Group (MRG): MRG was acquired in 2019 for around £300 million. That’s almost twice as much as InMotion and three-times WH Smith’s average earnings, so this was a very large acquisition. Marshall is another US-focused travel retailer, with stores in airports and tourist resorts across the country (but mostly in Las Vegas). This acquisition dramatically increased the size of the US business, making it about as large as the non-US international business.

MRG specialises in developing bespoke retail outlets for airports and tourist resorts that are more attractive to customers and landlords than the usual “cookie cutter” stores offered by most competitors, including its old competitor WH Smith. This ability is now being applied outside the US, with unique store design being a key part of recent winning bids for airport units in Spain, Italy, Belgium and Australia.

Taken together, these two acquisitions cost more than £450 million, which is about half of WH Smith’s total earnings over the previous ten years (£890 million). That’s quite close to the most I can stomach:

- Rule of thumb: Total acquisition spend over ten years should be less than total earnings

Although these acquisitions were large, I don’t think they were excessive, but I do think WH Smith should avoid making further large acquisitions until these two are well and truly bedded in.

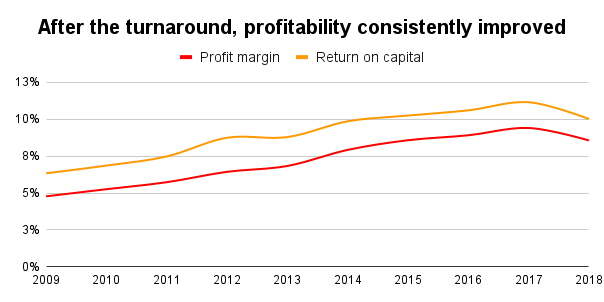

Profitability was also improving metronomically, until the pandemic struck

Consistent above average profitability is important because it’s a sign that the company may have durable competitive advantages. In other words, it’s a sign of quality. High profitability also means high earnings that can be used to fund higher dividends and higher growth rates.

There are lots of profitability ratios, buy I stick to the basics of profit margins and returns on capital. In WH Smith’s case, its long transformation over the last 15 years shows up as consistently improving margins and returns on capital.

Here’s a chart showing how profitability was improving in the years before the pandemic.

That improvement had two main drivers:

- High street improvements: Profitability in the high street business consistently improved as it transformed from a stodgy old-school retailer selling low-margin products into a much leaner, smarter retailer selling products at higher prices in order to generate acceptable returns

- Travel growth: The more profitable travel business grew from a small side business into the company’s core business, driving up overall profitability along the way

Over the ten years to 2018, WH Smith’s profit margins averaged 7.4% and that easily exceeds my minimum standard.

- Rule of thumb: Average profit margins over ten years should be above 5%

As for return on capital, it’s a different story. Although return on capital has consistently improved, it only reached double digit levels for a few years between 2014 and 2018. Over the full decade to 2018 it only averaged 9% and that’s a Yellow Flag because it breaks one of my rules.

- Rule of thumb: Average returns on capital over ten years should be above 10%

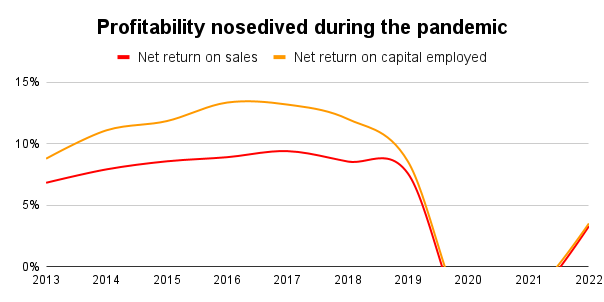

Although WH Smith did achieve double-digit returns on capital for a few years, those returns turned out to be short-lived. When the pandemic struck in 2020 and 2021, the company inevitably recorded very substantial losses and very negative profit margins and returns on capital.

With the pandemic now in the rear-view mirror, profitability has started to recover, but it’s still a long way short of pre-pandemic levels. That’s partly because the high streets seem to have structurally lower footfall because more people work from home, but it’s also because air travel is expected to take another year or two to fully recover.

This puts a serious dent in WH Smith’s profitability track record, but I don’t think that makes it uninvestable. Instead, I think the company was hit by a major black swan event, so I’m willing to overlook the two years of losses and two years of suspended dividends.

Improving profitability was driven by sensible management and competitive advantages

I said earlier that consistently high profitability was a sign (but not a guarantee) of durable competitive advantages. In this case, I do think WH Smith has more than one durable competitive advantage that makes continued success, particularly in the UK, more likely.

Reputation advantage: WH Smith is easily the best-known UK newsagent and stationer to the extent that I cannot think of a serious national competitor. Most people know what to expect from its stores and if you put a no-brand newsagents next to a WH Smiths, I’m pretty sure the WH Smiths will almost always come out on top. This brand power is a huge asset to the UK high street and UK travel businesses, which together contain the majority of the company’s stores and are responsible for the majority of its profits.

Reputation isn’t just brand awareness. It also comes from a company’s history, its relationship with suppliers, its position in the industry and so on. For example, I’m sure WH Smith mentioned that it has been a leader in UK travel retail for about 150 years when it was pitching for its first international travel units.

Size advantage: In the UK, WH Smith has a massive scale advantage over other newsagents, booksellers and stationers. This gives it a variety of advantages in terms of operational efficiency, perhaps most importantly its ability to extract useful data from over 1,700 stores (including international outlets) to help it optimise product choices and store layouts.

Outside the UK, WH Smith lacks brand power and scale, as its 1,700 outlets is far below that of competitors like Lagardere (OTCPK:LGDDF), which has almost 5,000 units. Despite this scale disadvantage, WH Smith has still managed to grow its international business both rapidly and organically and I think this is a sign that it may have another competitive advantage.

Skill advantage: Given its success against much larger international competitors, I think WH Smith may just be better at running convenience stores than its peers. That may be because of its near-death experience in the mid-2000s, where it had to dramatically improve or get taken over or die, but it could be a combination of scale and experience, as it’s been the UK’s leading newsagent, bookseller and stationer for the best part of 200 years.

However, while being more skilful is a valuable and rare ability (both of which are key ideas in the VRIO competitive advantage framework), I think its large international competitors should be able to replicate this level of skill if they tried hard enough, so this advantage may not be durable.

When a recession looms, people may stop flying but they’ll still buy essentials in the high street

Let’s take a step back and look at the broader picture, by which I mean the markets WH Smith operates in.

In terms of cyclicality, the high street business should be relatively defensive because it sells small-ticket impulse purchases like magazines or fizzy drinks to people as they walk down the high street. These purchase decisions are not massively affected by the broader economy because they’re a relatively small part of the customer’s disposable income.

In the larger travel business, the main customers are leisure travellers because commuters are usually in too much of a rush to stop and buy anything. Unfortunately, leisure travel is economically sensitive because holidays and days out are relatively big-ticket expenses and they can easily be deferred to next year when times are tough.

Given that WH Smith generates about two-thirds of its revenues from travel retail and more than that in terms of profit, I would classify this business as cyclical. That’s fine by me and I’m quite happy to invest in cyclical businesses, but I don’t like to invest in too many of them as I’m a defensive dividend investor at heart.

- Rule of thumb: Don’t have more than 50% allocated to cyclical companies

Travel retail is an attractive market with good long-term growth prospects

A company’s intrinsic value comes from its ability to generate earnings and dividends over the long-term, so as investors we need to think about the long-term prospects of a company’s core markets.

- Rule of thumb: Avoid companies where the core market is in long-term decline

In WH Smith’s case, the high street business has been in structural decline for many years and I think that’s likely to continue. However, I don’t think the high street business will shrink to nothing, because people will always need convenience stores where you can pick up this or that as you’re passing by.

Fortunately, WH Smith realised that its old core high street business was in structural decline more than a decade ago. Since then, the company has very successfully used the high street business as a cash cow to fund growth in the more attractive travel business, to the point where travel retail is now the core business.

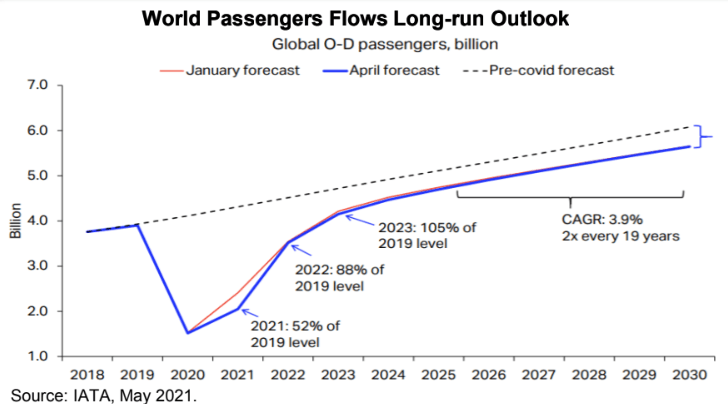

In UK travel there is still much room for growth, especially in hospitals where management expects most of the new UK units to be opened. Internationally, most of the company’s outlets are in airports and that’s a good place to be, because air travel is expected to recover back to pre-pandemic levels by 2024 and to grow by around 4% per year to 2030.

Longer-term forecasts have air miles travelled growing by about 3-4% per year to 2050, so despite the headwind posed by the need to decarbonise air travel, the industry is expected to grow ahead of the global economy for decades to come.

Technology and the internet are unlikely to significantly disrupt convenience retail

- Rule of thumb: Avoid companies where the core market is likely to be disrupted within the next decade or two

WH Smith is somewhat unusual for a store-based retailer because I think it should be relatively immune from disruption by internet retailers.

That wasn’t true 15 years ago, when 25% of its revenue came from the sale of arcane objects like CDs and DVDs that were destined to be replaced by online alternatives. But since 2003, the company has re-focused itself around convenience retail, selling products that people buy on impulse while they’re out and about. And until you can order something on Amazon and have Deliveroo deliver it to Platform 9 at Euston within three minutes, I think the convenience retail market should be relative free from technological disruption.

Acquisitions and pandemics have seriously weakened an already weak balance sheet

The last thing I want to look at is the company’s balance sheet.

The story here is that for most of the last two decades, WH Smith used very little in the way of borrowings and none at all between 2010 and 2013. Having no debt is prudent, but you could also call it inefficient because most companies can safely benefit from a little financial leverage.

Karen Swann left the business in 2013 and her replacement was more willing to boost returns using debt. WH Smith’s borrowings increased from zero in 2013 to £47 million in 2018, but that was still less than half of a single year’s average earnings (so a very prudent level of borrowings).

However, WH Smith is a store-based retailer that leases its stores, and a lease agreement is effectively a form of debt, where a store is borrowed in return for rental payments rather than money being borrowed in return for interest payments.

In 2018, WH Smith had £640 million of outstanding lease liabilities. If you combine leases and borrowings then the company had a debt to average earnings ratio of 7.6. That’s a Red Flag because it blows a big hole through one of my rules of thumb.

- Rule of thumb: The ratio of debts (borrowings and leases) to average earnings should be below 4.0 for cyclical companies

Unfortunately, WH Smith’s balance sheet has deteriorated significantly since then.

The deterioration began just before the pandemic, when management rolled the dice and took on hundreds of millions of pounds of debt to acquire InMotion and MRG. I think the acquisitions were sensible, but using debt to fund them wasn’t. That left WH Smith’s balance sheet in a more fragile state and that was exactly what the company didn’t need going into a global pandemic.

Of course, when the pandemic struck, travel was banned and the majority of WH Smith’s stores were closed, repeatedly, for many weeks. Management had little choice but to take on more debt and more equity (via a rights issue) just to keep the company afloat. That left it with total debts (including leases) of just over £1 billion in 2022, compared to average earnings of about £100 million. That’s a debt to earnings ratio of 10, which is well over double the 4.0 maximum I’m comfortable with. This is a very big Red Flag.

On that basis, I think WH Smith has a serious debt problem that makes it significantly riskier than it otherwise would be. Most of this can be blamed on the pandemic, but some of it comes down to management’s decision to use debt to acquire InMotion and MRG. I think that was a mistake, given WH Smith’s already large lease obligations.

At this point, I would normally end the review.

I do like WH Smith, I think it’s performed an amazing turnaround since 2003 and I think it probably is a quality company with durable competitive advantages. I also think it has a potentially bright future as an international travel retailer.

However, it is also carrying a huge amount of debt and that makes the business very risky. If we fall into a global recession for a year or so and if that leads to significantly lower air travel throughout 2023, WH Smith may struggle to repay those debts. And interest rates have gone up a lot, adding yet more risk. I don’t think WH Smith is going bust anytime soon, but it may have to carry out another rights issue to pay down some of its debt, and that would reduce the value of existing shares.

Having said all that, the review is almost done and I do like the company, so I may as well go ahead and come up with estimates for “fair value” and “good value”.

Estimating WH Smith’s fair value by estimating its future dividends

“Earnings are only a means to an end, and the means should not be mistaken for the end. Therefore we must say that a stock derives its value from its dividends, not its earnings. In short, a stock is worth only what you can get out of it. Even so spoke the old farmer to his son: A cow for her milk, a hen for her eggs, and a stock, by heck for her dividends. An orchard for fruit, bees for their honey, and stocks, besides for their dividends” – John Burr Williams, The Theory of Investment Value, 1938

To estimate the intrinsic value of a company, we need to estimate its future dividends using a discounted dividend model. In other words, a company is worth the sum of all its future dividends, with those dividends discounted by an annual rate of return to take account of the fact that one bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

If we start with the 2022 dividend, it was 9.1p. That’s well below the pre-pandemic 2019 high of 58.2p and that’s understandable. WH Smith has been to hell and back over the last two years and management responded, in part, by suspending the dividend for two years and it was only reinstated with the final dividend in 2022.

In the short term, the company now has to deal with high inflation and a potentially global recession. This isn’t great, but personally I don’t think the dividend is going to be cut or re-suspended because it’s already been rebased to a very cautious level.

On the assumption that WH Smith isn’t going bust (I don’t think it is) and that it isn’t going to carry out a large rights issue to pay down debt (it might do, but I’ll assume it won’t), the next question is, how quickly can the dividend recover to normal levels and what sort of growth is likely from there?

Answering that is made somewhat more difficult by the fact that WH Smith has four significant businesses (UK high street, Funky Pigeon, UK travel and international travel) that are heading in different directions at different speeds.

I don’t always model a company’s future down to the divisional level because in many cases it isn’t necessary, but in this case though, I think it would be sensible to have at least a ballpark idea of where each division might go in the years ahead.

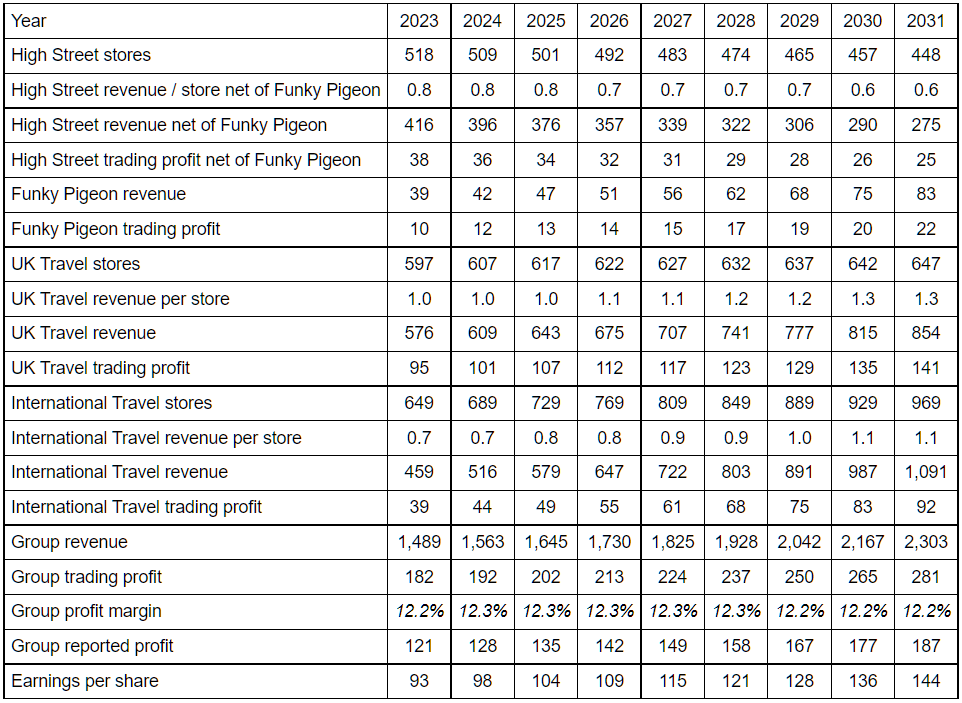

By combining past performance with management’s stated targets, I came up with what I think is a conservative and realistic set of assumptions for the performance of each major business between 2022 and 2031, based on trends and expectations for the number of stores, revenue per store and profit margin.

Here’s a table with all the data, which I’ll summarise below in case you don’t want to stare at a wall of numbers.

The short version of that model is that in terms of profit, the high street business declines by 5% per year, Funky Pigeon grows by 10% per year, UK travel grows by 4% per year and international travel grows by 10% per year.

The net result of all that is that EPS grows from an estimated 93p in 2023 to 144p in 2031, compared to a 2017 all-time high of 107p.

Ultimately, we’re interested in dividends, not earnings, so the next step is to estimate how much of those earnings need to be retained to drive growth and how much can be paid out as dividends. This will depend on the target growth rate and the company’s return on capital.

It’s a bit like a savings account. If you have a savings account with a 5% interest rate (a 5% return on capital) and you want it to grow by 5% per year, you need to reinvest all of the interest (earnings). If the interest rate is 10%, you only have to retain half the interest and you can pay out the other half to yourself as a “dividend”.

This is easy to work out with a spreadsheet, so if you’re interested in how this works, feel free to try out my Company Review Spreadsheet (on the free resources page).

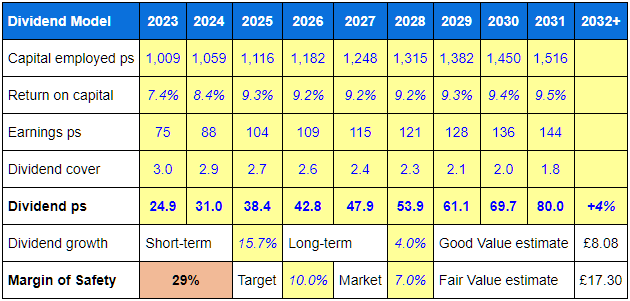

My goal is to come up with estimates for return on capital and dividend cover that are conservative and realistic given the company’s past performance and which also end up producing EPS growth similar to the estimates in the table above (i.e. growing to about 144p by 2031).

Here are the assumptions I came up with:

- Return on capital increases from a depressed 7.4% in 2023 back towards the double-digit highs seen shortly before the pandemic

- Dividend cover decreases from a very conservative 3.0 in 2023 to a more historically typical 1.8 in 2031

- Long-term growth remains at a relatively high 4% for at least ten years after 2031, thanks to its exposure to the high-growth air travel industry

Here’s the final model, which I’ll explain below.

As you can see, the model has WH Smith’s dividend growing from 25p in 2023 to 80p in 2031. The company’s all-time high dividend was 58.2p in 2019, so I think an increase to 80p by 2031 is both realistic and conservative. The model also matches the previous EPS estimate of 144p in 2031.

To estimate WH Smith’s intrinsic or fair value, we need to discount (reduce) those estimated dividends by a fair rate of return. I use 7% per year as the fair rate of return because that’s the long-term average UK stock market return. I also like to estimate a good value price, which discounts future dividends by my target rate of return of 10%.

The discounted dividends (which aren’t shown in the table above) are then added together to give the final fair value and good value estimates:

- Fair value estimate = £17.30

- Good value estimate = £8.08

As I write, WH Smith’s share price is £14.71, so the price is slightly below fair value.

To measure the gap between price and fair value more accurately, I use a Margin of Safety score. It works like this:

- If the price equals fair value, the margin of safety is zero

- If the price equals good value, the margin of safety is 100%

- If the price is halfway between good and fair value, the margin of safety is 50%

WH Smith’s share price is only slightly below my fair value estimate, so the margin of safety score is low at 29%.

This is another Red Flag because it fails my valuation rules of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only buy shares in a company if its margin of safety is above 66%

- Rule of thumb: Consider selling a company’s shares if its margin of safety is below 33%

With WH Smith’s price currently in my “sell zone”, I won’t be looking to buy its shares anytime soon.

WH Smith may be a quality company but its balance sheet and valuation are problematic

This was a long review so round things up, I’ll summarise the yellow and red flags that came up along the way:

- Yellow Flag: The speed and consistency of WH Smith’s growth isn’t up to my standards, but that’s mostly down to the pandemic

- Yellow Flag: Returns on capital averaged 9% before the pandemic, failing (slightly) to meet my 10% minimum

- Red Flag: The debt to average earnings ratio is about 10x, more than double my ceiling of 4x for cyclical companies

- Red Flag: The estimated margin of safety is 29%, which falls into my “sell zone” (0% to 33%)

I could live with the slightly weak returns on capital because I do think the company has durable competitive advantages and I think it could produce consistent returns on capital above 10% in the future.

The debts and valuation are bigger problems, so I won’t be buying WH Smith today. Instead, I’ll add it to my watchlist where I can keep an eye on it over the next few years.

My personal experience as a WH Smith shareholder

For all the reasons mentioned above, I recently removed WH Smith from my personal portfolio and the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio at £14.29 per share. I originally bought WH Smith back in 2018, at £19.05 per share. Here’s the original purchase review (PDF).

The investment wasn’t a disaster, but the annualised return was -4.3% so it was disappointing. With the benefit of hindsight, here’s where things went wrong:

(1) Weak valuation method

When I purchased WH Smith in 2018, I didn’t value companies using discounted dividend models. Instead, I valued them using their rank on my stock screen and by looking at ratios like PE10 and PD10. Although I still think that approach is okay, I now think discounted dividend models can be significantly better.

After selling WH Smith, I went back and built a dividend model using its financial data up to 2018. That model estimated WH Smith’s fair value in 2018 to be £17.78, compared to my purchase price of £19.05, so on that basis, I think I slightly overpaid.

The good news is that I switched to using the more theoretically correct and generally more accurate discounted dividend models in early 2021, so hopefully my valuation methodology should be less problematic in future.

(2) Weak balance sheet analysis

Back in 2018, I didn’t look at lease liabilities. That’s unfortunate, because most of WH Smith’s debts are lease liabilities. I first learned about the problems that large leases can cause when my investment in The Restaurant Group blew up in 2019 (here the sale review (PDF) for that one). As with valuations, this should be less of a problem in future because I’m well aware that large leases can be toxic.

(3) Bad luck

When someone blames bad luck for a poor result, it’s often because they cannot admit to their mistakes. However, most of WH Smith’s recent problems were caused by the pandemic and I think I can reasonably call that bad luck.

This once-in-a-century event had a significant impact on WH Smith’s travel business and it had a material impact on the company’s future dividends and fair value. In other words, WH Smith’s future dividends and fair value are now be lower than could reasonably have been expected in 2018, because it had to take on additional debt and equity just to stay afloat and both of those will reduce dividends per share over the medium term.

Black swan events like pandemics are hard to plan for, so the best defence is diversity, which is why I like my portfolio to have reasonably high levels of industrial diversity.

- Rule of thumb: There should be no more than three holdings from any one industry

- Rule of thumb: No more than 50% of the portfolio’s aggregate revenues should come from any one country

An investor’s job is to allocate their capital as effectively as possible, so most of the proceeds from the sale of WH Smith have already been reinvested into a more attractive holding which for now shall remain nameless.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year

This will probably be my last post for 2022. I’ll be kicking 2023 off with the usual year-end reviews of my portfolio, the UK & US stock markets and the UK housing market.

As always, thank you to everyone who commented on the blog, I hope you (and everyone else) have an enjoyable Christmas and a profitable new year.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Comments 1