In the past nine months inflation has surged, stock prices have fallen and global growth has stalled. Everyone seems to be hurting — everyone, that is, except oil companies.

While the energy crisis sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has pushed up the cost of fuel, electricity and thousands of other everyday items, fossil fuel producers, and their shareholders, have got richer.

Profits at the largest US oil company, ExxonMobil, tripled in the third quarter to a record of nearly $20bn, bringing its earnings for the year to more than $43bn. Shell, Europe’s largest, has made $30bn this year, including $9.5bn in the three months to September. BP is on course for possibly the most profitable year in its history.

In response, politicians from Washington to London to Milan have found themselves threatening or enacting the same policy response: windfall taxes.

“Their profits are a windfall of war — a windfall from the brutal conflict that is ravaging Ukraine and hurting tens of millions of people around the globe,” US president Joe Biden said this week as he promised increased levies on producers unless they help cut US fuel costs.

Rishi Sunak, as UK chancellor, said it was “fiscally responsible” to tax oil and gas producers’ “extraordinary” earnings when he announced an energy profits levy in May. Five months later, Sunak, now prime minister, is considering increasing the levy from 25 per cent to 30 per cent and extending it to 2028.

In Europe, the EU introduced a “solidarity contribution” levy of at least 33 per cent of “surplus taxable profits” made by fossil fuel companies. Italy has also introduced a 25 per cent windfall tax on energy company profits, while Spain has proposed a 1.2 per cent additional tax on energy company sales, as well as a 4.8 per cent levy on bank profits.

The politics of windfall taxes are simple: few voters object to corporations — particularly oil majors — being squeezed after profiting during hard times. But designing and implementing them is less so, particularly when companies have global earnings and investment in new, greener sources of energy is needed.

A recurring theme

Windfall taxes are not new. In the first years of the first world war at least 22 countries, including the UK, US, France, Italy and Germany adopted some form of extra tax on “excess” corporate profits.

During the second world war, an excess profits tax in the US generated 22 per cent of government tax receipts in 1943, equivalent to 2.2 per cent of gross domestic product, according to the IMF.

In the energy industry, government efforts to capture greater tax revenue during periods of high prices are a recurring theme. Many producing countries, such as Australia, Nigeria and Brazil, have tax regimes that include a mechanism to ensure the state gains if prices rise.

In the UK, which taxes profits rather than production, the Treasury has regularly tweaked the tax rate over the past 50 years depending on the oil price, explains Graham Kellas, head of fiscal policy research at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

“The UK oil and gas tax policy since it began has basically been to keep an eye on what’s happening with prices and adjust the tax rates when you feel that the price level has shifted,” he says.

Most recently, then chancellor George Osborne in 2011 raised the supplementary tax rate paid by oil and gas producers from 20 per cent to 32 per cent after oil prices spiked. It was then cut to 10 per cent between 2014 and 2016 as prices fell.

Taxing profits rather than production enables the UK to “take more later” and continue to attract investment, but the “ad hoc” rate changes also create uncertainty, says Kellas.

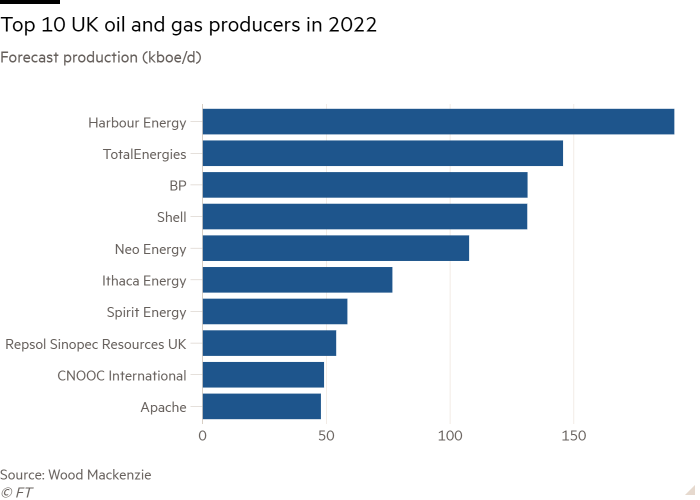

So far the energy profits levy in the UK has had a mixed impact. This week, BP, which is the third-largest oil and gas producer in the North Sea, said its UK business expected to pay about $2.5bn in taxes in 2022, including about $800mn under the new levy.

Private equity-backed Harbour Energy, which is the UK’s biggest producer, expects to pay $900mn in UK taxes this year, including $400mn under the levy.

![US president Joe Biden: ‘The [energy groups’] profits are a windfall of war — a windfall from the brutal conflict that is ravaging Ukraine and hurting tens of millions of people around the globe’](https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/https%3A%2F%2Fd1e00ek4ebabms.cloudfront.net%2Fproduction%2F337cb9e0-5398-42c7-b04a-983ac18cd0ce.jpg?fit=scale-down&source=next&width=700)

In contrast, Shell, which like BP produces about 120,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day in the UK, has paid no UK taxes at all this year. Investments in new production and costs associated with decommissioning old fields have cancelled out all UK profits, it said. In fact, Shell has paid no taxes on its UK oil and gas production since 2017.

Perhaps aware of the poor optics of paying no tax in the UK while returning billions of dollars of record profits to shareholders, outgoing chief executive Ben van Beurden has said his UK-headquartered company is willing to pay more.

“[Governments] will be looking at companies like us who benefit from the volatility and the prices that we see, to fund the programmes they are rolling out,” van Beurden said last week after Shell reported the second-highest quarterly profit in its history. “I think we have to accept it and we have to embrace it.”

That view, however, is not shared across the industry. While Shell generates profits around the world, many of the producers in the North Sea are more dependent on their UK revenues.

“It won’t be the oil majors who will bear the brunt of the impact of unpredictable windfall taxes,” says Iain Pyle, investment director at UK-based asset manager Abrdn, a top 10 shareholder in the North Sea gas group Serica Energy.

“Instead, the burden will fall on smaller domestic producers and on local service companies and private contractors,” he says. “These companies and their supply chains are less able to withstand a five-year period of high taxation and cannot simply relocate.”

Sam Laidlaw, founder and executive chair of Neptune Energy, which produces about 12 per cent of its oil and gas in the UK, says introducing higher taxes is OK if it is clear why they are being introduced and for how long.

The EU’s “solidarity contribution” will only apply to profits made in 2022 or 2023, he says. In contrast, the UK’s energy profits levy applies to the end of 2025 and might be extended to 2028.

“We have had one change [in the UK tax regime] already this year, which was introduced at pretty short notice with very limited consultation,” Laidlaw says. “If we have further changes, that really undermines the whole stability question.”

What government wants

There’s a contradiction at the heart of many western governments’ approach to the fossil fuel industry since the start of the crisis.

After years of calling on the sector to reduce emissions, policymakers now want companies to boost supply, while still urging the same executives to deliver a long-term transition to greener fuels.

Global profits in the third quarter

Despite a commitment to cut emissions to net zero by 2050, the UK still wants to encourage investment in oil and gas production that it says is necessary for the country to have sufficient sources of energy until it can fully transition to greener forms of power.

As a result, the energy profits levy includes a generous “super deduction” for investments in new oil and gas production that rewards companies with an overall 91p tax saving for every £1 they invest.

Professor Michael Devereux at the Oxford university Centre for Business Taxation says this has, in effect, created a subsidy for fossil fuel projects that otherwise would not go ahead. “A subsidy could be justified for investment in renewables, but it is much harder to justify for investment in oil and gas,” he says.

In the US, a Biden administration that initially talked of curbing new drilling and accelerating a transition from oil has shifted to threatening to penalise companies unless they power up more rigs. “If they don’t, they’re going to pay a higher tax on their excess profits and face other restrictions,” Biden said this week.

Yet most analysts see the threat of new federal taxes on US oil company profits as little more than campaign rhetoric ahead of midterm elections next week.

An act of Congress would probably be required, which would meet resistance from some Senate Democrats and blanket opposition from the Republicans, who polls suggest will control at least one of the houses of Congress after Tuesday’s vote.

State-level interventions are more plausible, particularly if high prices persist, says Kevin Book, managing director at Clearview Energy Partners, a Washington advisory firm.

“High prices tend to make governments grabby, and a recession could strain state and local government finances,” he says. “In that context, even some producer states might begin to eye industry profits — potentially leading to a . . . modification of existing incentives, if not new levies.”

Sowing the windfall

Windfall taxes are often not a guaranteed revenue raiser. Italy’s levy brought in billions less than anticipated, as many energy companies simply refused to pay and brought legal challenges against the government.

Part of the challenge for governments is that the eye-popping earnings figures from the likes of BP and Shell, which provoke the most outrage from voters, are global profits and the portion subject to UK tax is much smaller. Convention dictates that countries do not tax foreign profits, which are normally taxed in the jurisdiction where those profits are made.

BP reported quarterly earnings of $8.2bn this week but perhaps 10 per cent was generated in the UK, says Kellas at Wood Mackenzie. (BP, like Shell, does not break down its profits by geography.)

Murray Auchincloss, BP’s chief financial officer, says that although people are “understandably focused on our global profit levels” at a “difficult time for society”, his company does not shirk its responsibilities to the UK taxpayer.

He says that in the UK, $2 out of every $3 the company makes goes to the government. Worldwide, BP paid $5bn in taxes in the third quarter at an average tax rate of 37 per cent, he adds.

The rewards are not only going to shareholders, but being invested in the energy transition, he notes. BP plans to spend £18bn in the UK in the next decade, primarily in renewables and technologies such as carbon capture and storage.

“I get that governments have a very difficult challenge right now,” he says, “but really we are just focused on trying to invest and pay taxes.”

Still, as the social costs of the crisis grow, some are calling for more radical solutions. Dan Neidle, a former tax specialist at Clifford Chance who founded the non-profit Tax Policy Associates, argues that although taxing foreign profits is normally considered “bad manners”, a one-off exception could be made if taxing the domestic profits of UK-headquartered energy companies proves insufficient.

It could be done, he says, “if we credibly say it’s a one-off and won’t be repeated”. The risk of companies relocating their headquarters to avoid taxation would be lower than people think, he argues, adding that double taxation treaties could be used to prevent any group paying tax twice on the same profits. “Shell is crying out to be taxed more,” he says.

Additional reporting by David Sheppard