The time has arrived for the annual climate tamasha, Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), to be held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. With a quarter-century of COPs behind us, one can forgive the public for feeling a bit jaded as COP27 rolls around. Solutions to the climate crisis appear as far away as they were a decade or even two decades ago. Just this week, the UN Environment Programme noted that we could expect a warming of 2.8 degrees Celsius based on current national policies in place, and pledges for enhanced policies might reduce this to 2.4-2.6 degrees Celsius, still well above the UNFCCC enshrined upper limit of 2 degrees Celsius with an aspiration of 1.5 degrees Celsius warming.

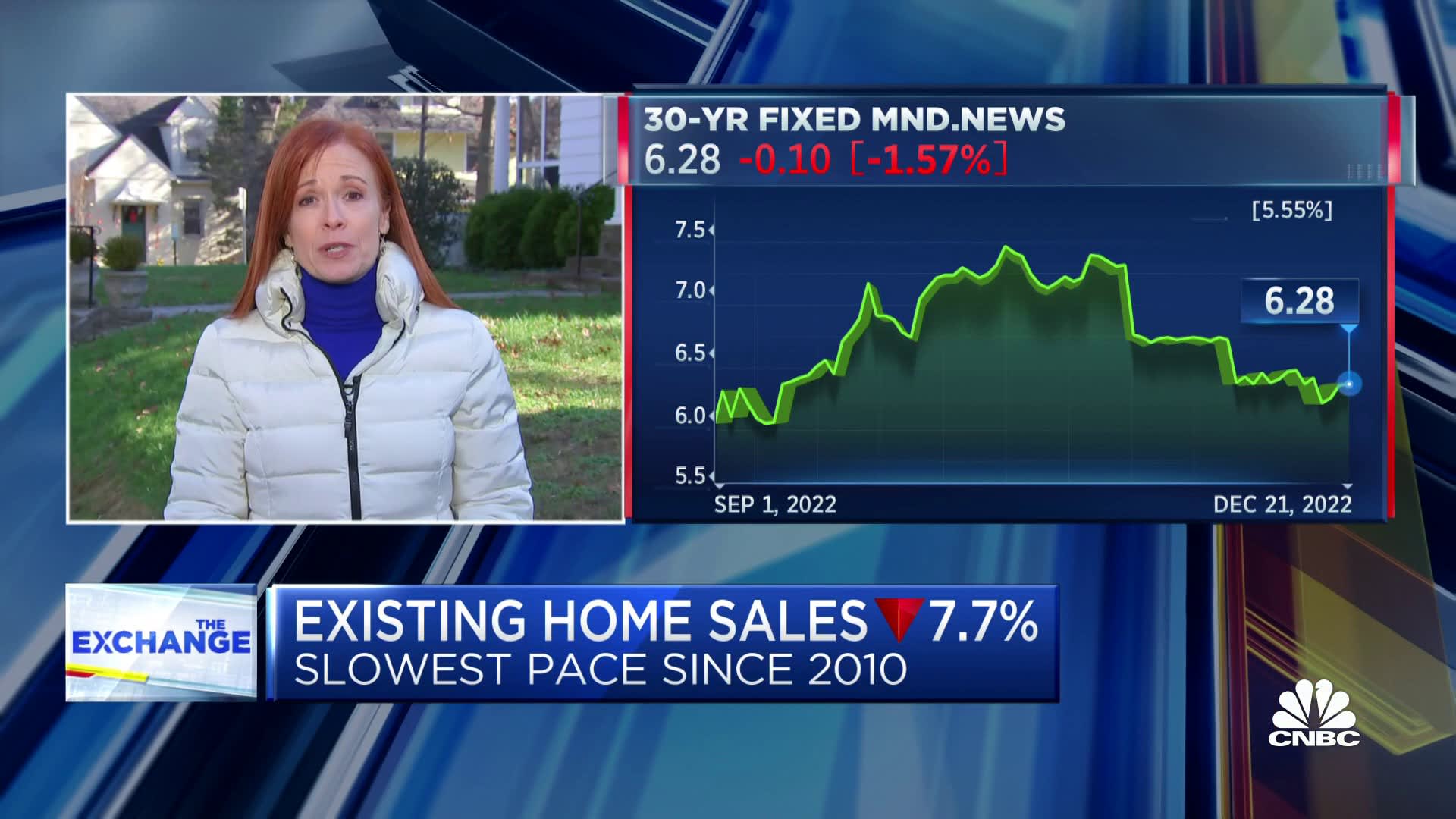

Yet, there are also signs that the super-tanker, the world’s energy system, is turning around. The cost of solar power and battery storage for electricity is down 85% over the last decade. As a result, more money is now being invested in renewable energy than fossil fuel energy. But there is a long way to go to overcome the current dependence on coal for electricity, and oil for transport, around the world.

The annual COP serves as an annual health check, as Rachel Kyte of Tufts Fletcher School told me in a podcast. It is a focal point for technical assessments of progress and a place where technical rules that translate political agreements into action are made. However, COPs also have an explicitly political side, and COP27 in Egypt is likely to be dominated by the political conversation for at least two reasons.

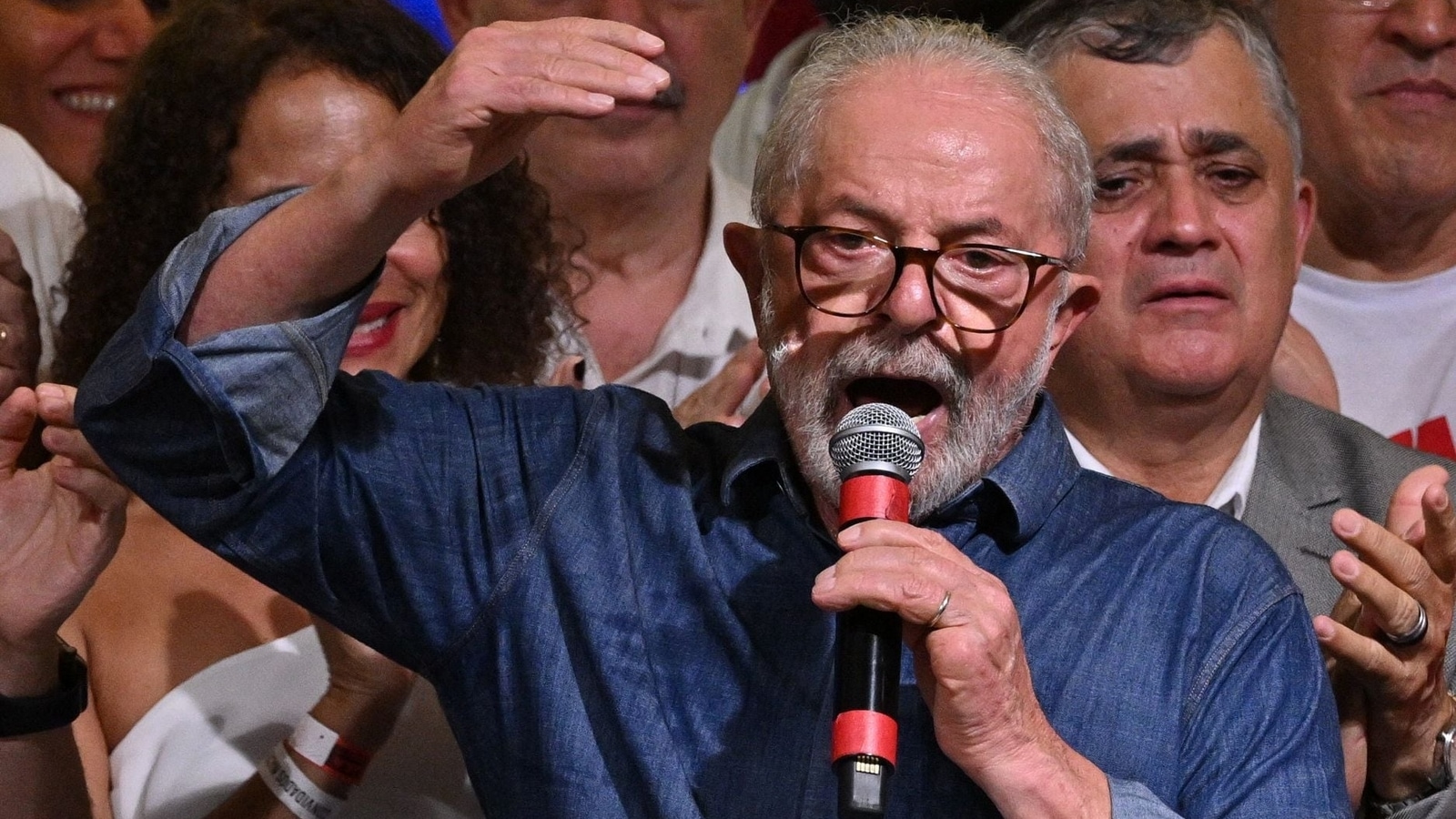

First, COP27 may be the first COP to be unambiguously held in the era of climate impacts, as veteran climate watcher Saleemul Huq from Bangladesh said in his Centre for Policy Research podcast. This year witnessed floods in Pakistan, heatwaves in South Asia and Europe, wildfires in Australia and California, and Hurricane Ian in the United States (US). Developing and vulnerable countries are mobilised to argue for greater attention to the damages resulting from climate impacts.

Second, COP27 will occur during a time of multiple and reinforcing crises — economic historian Adam Tooze has popularised the term polycrisis — when the appetite for global give-and-take is at a low ebb. In addition to the climate crisis, we face the Russia-Ukraine war, an associated energy security crisis, heightened fears of nuclear warfare, growing tensions between the US and China over Taiwan, surging commodity prices, a growing food crisis and, of course, the continued shocks of Covid-19. There is a considerable risk of the climate crisis being pushed to the back-burner.

Between these two pressures, this COP will likely see a resurgence of North-South tensions. Europe enters COP27 on the back foot after reopening coal-fired plants and expanding gas subsidies to see their populations through the winter. African fossil fuel producers are particularly exercised at this rollback because developed countries lobby to cut off development finance for African gas fields. Vulnerable countries that have done little to contribute to the climate crisis have demanded that the climate crisis be linked to debt relief.

Two political issues are likely to dominate COP, both of which are important for the developing world, and on which little progress has been made. The first is “loss and damage”. This refers to the fact that despite efforts to reduce emissions and adapt to a warming world, there are residual damages that countries increasingly face. How are these to be ameliorated? Developed countries are anxious to avoid the language of compensation or reparation, fearing that they would be signing a blank cheque. Yet, the manifestly unfair nature of climate consequences demands redress. In the procedure-heavy metric of COPs, winning an agreement to start negotiating a facility for loss and damage, something that the Glasgow COP failed to achieve, would in itself be a victory.

The second, finance, is even more complex. If capital-scarce developing countries are to pivot to low-carbon economies and invest in greater adaptive measures, they require external financial support. So far, developed countries have failed to deliver on even the relatively limited pledge of $100 billion a year. Discussions on finance have increasingly shifted away from COPs to forums such as the annual meeting of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). And, part of the debate is whether these institutions can play a growing role in mobilising finance. While open to these changes, and even encouraging them, many developing countries also insist that the finance debate cannot only be about mobilising private capital, it must also include public funds in the form of grants and, perhaps, highly concessional loans.

The Sharm el-Sheikh COP will be watched closely for progress on these two issues, even as the usual conversation on mitigation, adaptation goals, carbon market rules and other agenda items continue in the background. Both issues are important for India, which has historically been a standard bearer on the issue of finance, but has been less clear in its stance on loss and damage. At a time of global churn, and the potential for greater North-South jostling, the political messages that emerge from Sharm el-Sheikh may shape future COPs, and the climate agenda for some time to come.

Navroz K Dubash is professor, Centre for Policy Research

The views expressed are personal