One of Andrew Cuomo’s more dubious legacies was his push to “transform” mental health in New York by getting rid of psychiatric hospital beds that he said New York didn’t need. Statewide, there were about 10,200 beds in 2014; now there are about 9,100.

Though previous waves of “deinstitutionalization” had strewn chaos in the streets of New York, Cuomo argued that this time it would be different.

It wasn’t.

As beds declined, mental health-related pressures grew on other systems, such as transit, homeless services, police departments, and jails. The promise of community-based care as a better, cheaper alternative to psychiatric hospitalization proved, once again, elusive.

Throughout the 2010s, New York lost psych beds on two fronts: beds in state-run “psychiatric centers” that specialize in inpatient mental health care, and in general hospitals.

Hospital cost-cutting

Back in 2010, the New York Department of Health restructured Medicaid to incentivize general hospitals to reduce average lengths of stay for psych patients. The more days someone remained hospitalized, the less that Medicaid would reimburse that hospital for his care.

Hospital systems responded by increasing discharges and cutting beds entirely in the interest of pursuing more profitable “lines of business.” During the recent pandemic, many systems converted psych beds for COVID overflow. This raised fears that those beds would never be brought back post-COVID.

Back in February, Gov. Hochul announced a $27.5 million boost to Medicaid reimbursement for inpatient psychiatric care in general hospitals. This was done to incentivize the return of those beds converted during COVID and to bring a measure of stability to inpatient mental health in New York.

As for beds in state psychiatric centers, one reason why New York has so often targeted them for cuts is it could not bill Medicaid, and thus the federal government, for the cost. That is due to a long-standing provision in Medicaid known as the “IMD Exclusion.”

In 2018, the Trump administration authorized states to apply for a waiver from the IMD Exclusion.

Earlier this month, the Hochul administration announced plans to apply for a waiver. New York will not be using waiver funds to “revive the asylum” nor would federal Medicaid officials even allow that. New York cannot use the new funding for adults who need long-term institutionalization.

But, on net, New Yorkers should view more Medicaid funding for inpatient psychiatric care as a necessary condition of mental health reform.

Further progress will require an even more decisive break with Cuomo-era mental health policies. Hochul has not repudiated Cuomo’s “transformation plan” and she even touted, in her budget, the “success” of her predecessor’s policy that resulted in cutting hundreds of “unnecessary, vacant inpatient beds” from psychiatric centers.

Establishment conflict

To many New Yorkers, the need for more psychiatric hospitalization to respond to the current crisis may seem obvious. But that view is not shared by many mental health professionals, who disdain the very topic of psychiatric crisis.

Mentally ill people in crisis behave erratically and sometimes violently. Thus focusing on them, per the mental health establishment, perpetuates “stigma.” The establishment prefers the themes of prevention and recovery.

From their perspective, the best way to fight stigma is, whenever psychiatric crises make headlines, to change the subject as quickly as possible and refocus attention on programs that support people in recovery and can prevent people from falling into crisis in the first place.

But, as former National Institute of Mental Health director Thomas Insel explained in his recent book “Healing,” “recovery may be an important goal, but it feels irrelevant to someone in crisis. If our house is on fire, we need a fire extinguisher, not a three-part plan for renovation.”

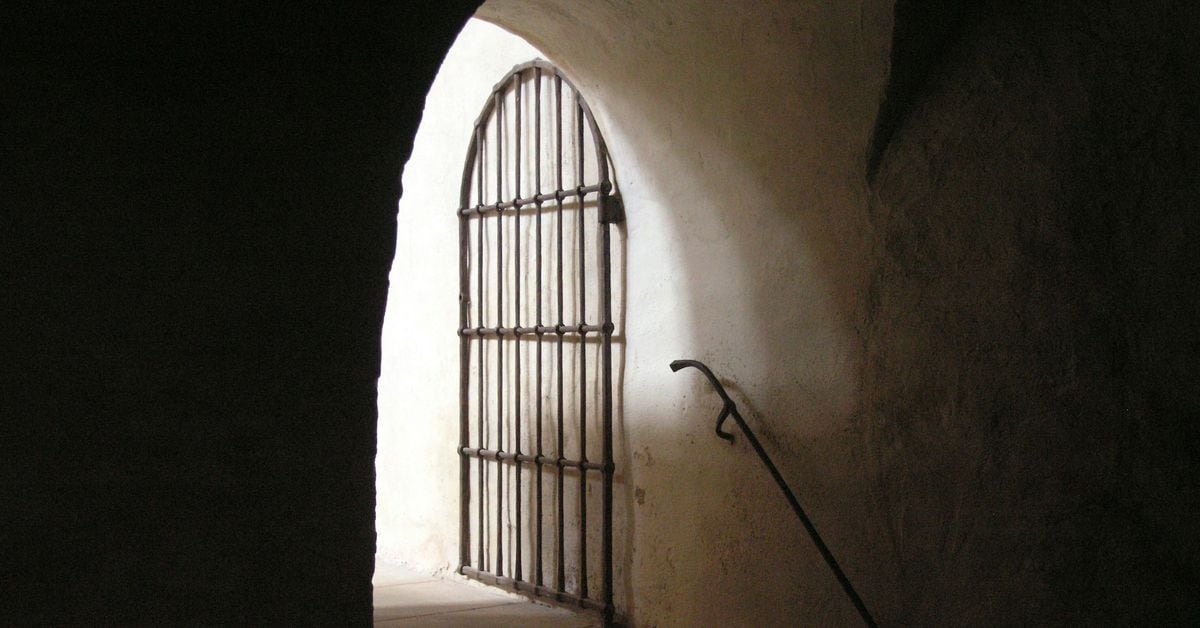

That has to start with hospitals. There are now about 1,000 seriously mentally ill people in city jails. Any serious solution to the “criminalization of mental illness” must involve psychiatric hospitalization, which is more humane than incarceration. And, for the most troubled mentally ill offenders, it’s much more viable than community services.

However urgent it may have once been to scale back the old “snake pit” asylums, more urgent, now, is New York’s lack of beds. Sometimes, respecting someone’s civil liberties is indistinguishable from abandoning them. New York plainly has a mental health crisis, and psychiatric hospitals are the definitive crisis response program.

Stephen Eide is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and author of “Homelessness in America.”