ROME, Jan 12 (IPS) – “We are the mothers, daughters and sisters of the missing and murdered Baloch. We are thousands.” Mahrang Baloch, a 28-year-old doctor from Pakistan’s Balochistan province, is blunt when introducing herself and the rest of a group protesting in central Islamabad.

“We are asking for an end to enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. We also demand the elimination of private militias,” the young woman explains in a phone conversation with IPS.

Baloch and the group arrived after a march that started in Balochistan last November. Nested in the country’s southeast and sharing borders with both Afghanistan and Iran, it’s the largest and most sparsely populated province in Pakistan, enduring the highest rates of illiteracy and infant mortality. It’s also the one most affected by violence.

Mahrang Baloch stresses that the trigger for the protest was the murder of a young Baloch man last November while he was in police custody. Following a two-week sit-in, the group decided to take the protest beyond the local province, embarking on a march to the Pakistani capital.

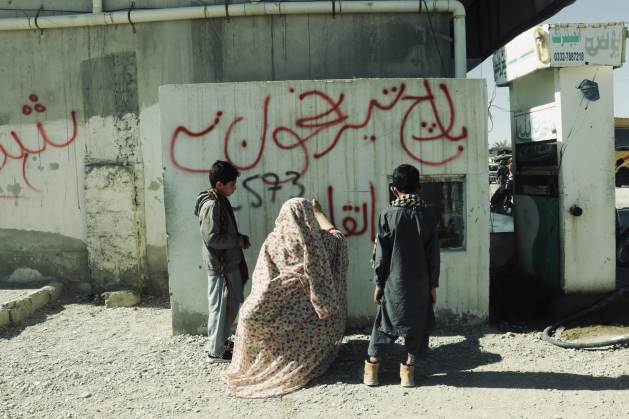

Clad in colourful traditional Baloch costumes and bearing portraits of their missing relatives, they received the warmth and support of tens of thousands along the way. However, the march was eventually blocked at the gates of Pakistan’s capital on December 20.

It was then that a police cordon permanently cut off their path on the outskirts of the city. The protesters refused to disband, so security forces responded with sticks, water jets and made hundreds of arrests.

Many women were dragged onto buses that took them back to Quetta, the provincial capital of Balochistan – 900 kilometres southwest of Islamabad. The rest set up a protest camp in front of the National Press Club, in downtown Islamabad.

After spending several hours in police custody, Baloch was eventually released. “We have carried the mutilated bodies of our loved ones. Several generations of us have seen much worse,” the young woman stresses.

She claims to be “mentally prepared” for the possibility of joining the long list of missing persons herself. “We have reached a point where neither forced disappearances nor murders can stop us,” adds the activist.

Mutilated and in ditches

Divided by the borders of Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, Balochistan is the land of the Baloch, a nation of 15-20 million with a distinct language and culture. After the British withdrawal from India, they declared a state of their own in 1947, even before Pakistan did. Seven months later, however, Balochistan would be forcefully annexed by Islamabad.

Violence has been rife ever since.

In a report released on January 2023, Human Rights Watch accused Pakistani security forces of committing “serious human rights violations which include arbitrary arrests and extrajudicial executions.”

In November 2021, Amnesty International published a report, titled “Living Ghosts,” calling on Islamabad “to end policies of enforced disappearances as well as secret and arbitrary detentions.”

Baloch human rights organization Voice for Baloch Missing Persons(VBMP) points to more than 7,000 missing people in the last two decades.

It was exactly for that reason that Mahrang Baloch was first imprisoned at 13, when she was protesting the disappearance of her father, Gaffar Lango, in 2006 in Quetta. After his release, Lango would be kidnapped again three years later. His body was found savagely mutilated in a ditch in 2011.

Next on the list was her brother Nasir, who was abducted in 2018. “That was a turning point for me. It was clear that no one was safe, that it could happen to anyone,” recalls the activist.

This square-jawed woman has become one of the drivers of change that the traditionally conservative Baloch society is undergoing through civil platforms such as the Baluche Unity Committee (BYC). They launched this protest.

From a less visible position, Saeeda Baloch, a 45-year-old Baloch woman who works for an NGO she prefers not to disclose, has devoted herself to raising funds to offer food and shelter to the participants. Her reasons are powerful.

“My husband was shot to death in 2011 when he was working collecting information about the disappeared and the killed. Moreover, his brother and my nephew have been missing since 2021,” Baloch explains to IPS by phone from Quetta.

He says the initiative has been highly successful “despite the violence they had to face in Islamabad.”

“Women have taken to the streets, many of them spending sub-zero nights with their babies. I can’t think of a more eloquent image of the determination of our people,” says the activist.

Solidarity

It was not the first time that Baloch men and women marched to the capital of Pakistan to protest over enforced disappearances. In October 2013, an initiative that started in the permanent protest camp of Quetta turned into a foot march to Islamabad.

It was led by a 72-year-old man known as Mama Qadeer. His son’s body was recovered 800 kilometres from Quetta, where he had been kidnapped. He had two gunshot wounds to the chest and one to the head, cigarette burns on his back, a broken hand and torture marks all over his body.

The figures of the so-called Great March for the Disappeared were as impressive as they were terrifying: 2,800 kilometres in 106 days during which 103 new unidentified bodies appeared in three mass graves.

“What differentiates both protests is the great participation of women in the last one and, above all, its leadership,” Kiyya Baloch, a Norway-based journalist and analyst of the Baloch issue explains to IPS by phone.

“This last march has already become a movement. Other than gathering great support in Balochistan, the Baloch who live in the province of Punjab, historically more silent, have also mobilized for the first time,” the expert emphasises.

The expert also highlights the support received from sectors of Pakistan’s also neglected Pashtun minority, as well as from international personalities including activists Malala Yousafzai and Gretha Thunberg, and the writer Mohamed Hanif.

The renowned British-Pakistani novelist made public that he had returned an award he had received in 2018. “I cannot accept this recognition from a State that kidnaps and tortures its Baloch citizens,” Hanif posted on his X account (formerly Twitter).

So far, the Pakistani government has turned a deaf ear.

In a televised appearance in January, Pakistani Prime Minister Anwar-ul-Haq Kakar referred to the protesters as “relatives of the terrorists” before adding that “anyone who supports the protest or writes about it should join the guerrilla.”

“Enemies of humanity”

At 80 years old, Makah Marri set foot in the capital of Pakistan for the first time in her life in the heat of the protest. She does not even speak Urdu – the country’s national language – but she is a well-known face at the numerous protests for the missing held in Balochistan.

She misses her son, Shahnawaz Marri. She has not heard from him since he was taken away in 2012. “What the relatives of the disappeared suffer is daily mental torture,” Marri recalls over the phone to IPS from Islamabad.

The images of the old woman, lifting the photo of her son above her head or being treated on the floor after fainting, have gone viral on social media. Today, she takes advantage of the conversation with the press to ask the rest of the world for “attention and support” for their cause.

The “enemies of humanity,” she emphasizes, not only took away her son, but also the father of her grandchildren.

© Inter Press Service (2024) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service